ABS Plastic vs Nylon: Which Is Stronger, Durable, and Better for Real-World Applications?

Choosing between ABS plastic vs Nylon determines whether a part fails under stress or thrives in its environment. Make the wrong call and you pay twice: once in material price and again in scrap, rework, warranty returns, or downtime.

ABS delivers predictable stiffness, solid impact resistance, and tight tolerances in dry, indoor conditions.

Nylon delivers higher tensile strength, better fatigue life, and stronger wear performance when heat, friction, or repeated loading dominates.

Use ABS for rigid housings and cosmetic parts; use nylon for gears, hinges, and wear surfaces under load, heat, or vibration.

Validate moisture conditioning and constraints before ordering.

Quick Verdict

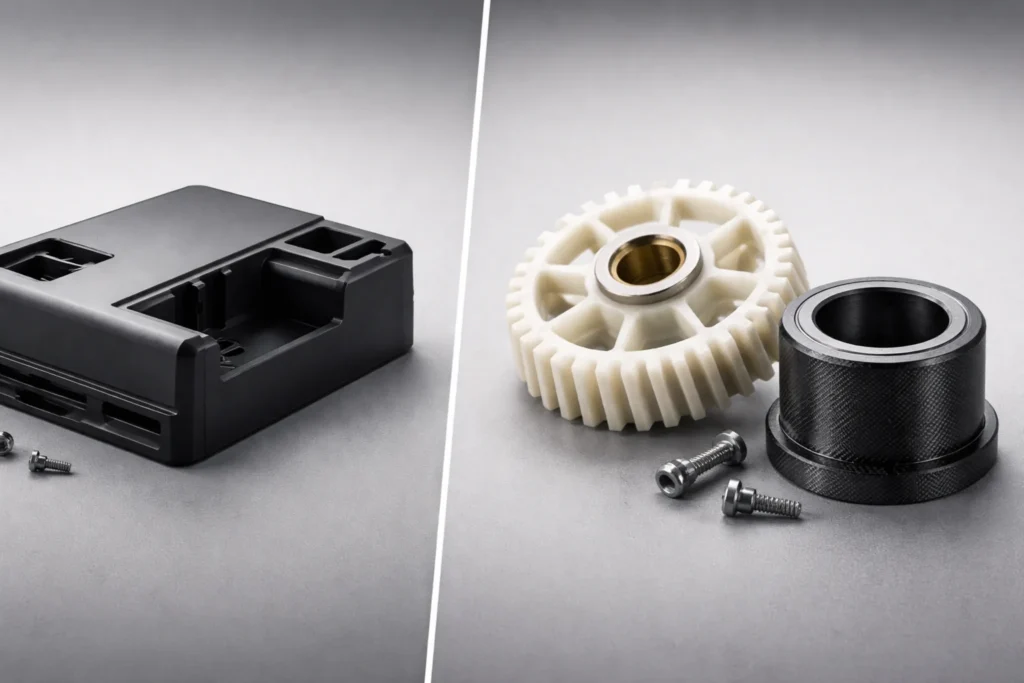

When ABS Plastic Is the Better Choice

Choose ABS when you need stable geometry, clean cosmetic finish, and controlled cost in dry environments. It holds tolerances well, machines cleanly, and resists impact without moisture-driven drift.

It is the safer choice for housings, brackets, clips, and cosmetic enclosures where repeatability matters more than peak strength.

When Nylon Is the Better Choice

Choose nylon when the part carries load, sees friction, or cycles under vibration. It wins on tensile strength, fatigue life, and wear resistance.

Many grades also run hotter before softening, which matters for gears, bushings, and functional components that must survive mechanical abuse.

The tradeoff is moisture uptake, which changes stiffness and dimensions unless you design and condition for it.

If you need “stronger,” nylon is typically the answer.

If you need “more predictable” with lower dimensional risk, ABS is the answer.

For production decisions, treat nylon as a performance material and ABS as a control material.

ABS vs Nylon Choice (Executive Table)

| Feature | ABS | Nylon |

| Strength | Good impact strength; moderate tensile strength | Higher tensile strength; strong fatigue resistance |

| Heat | Typical HDT around 90–105°C (grade-dependent) | Nylon 6/6 HDT commonly 160–190°C; Nylon 6 often 140–170°C |

| Cost | Usually lower; easier processing | Often higher; drying/conditioning adds cost |

| Finish | Excellent surface finish; paints well | Functional finish; paint adhesion varies by grade |

| Dimensional Stability | High (predictable in dry service) | Moderate to Low (moisture dependent; design must account for swelling) |

Core Material Differences That Actually Matter

Molecular Structure & Mechanical Behavior

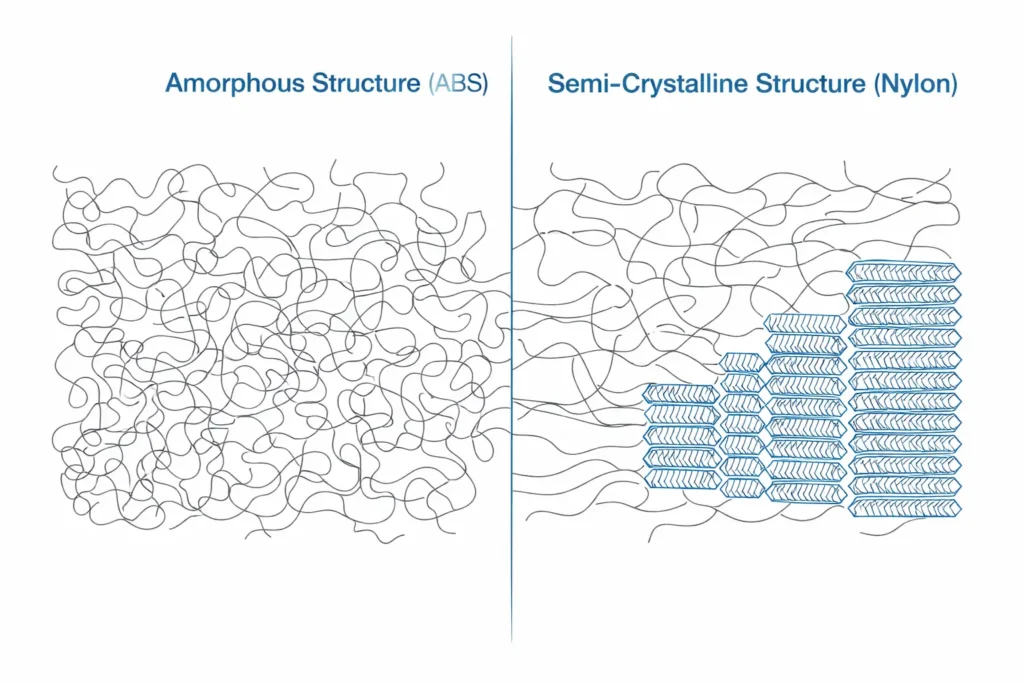

ABS is amorphous. Its polymer chains sit in a tangled mess with no organized crystalline regions and no true melting point. It softens as it approaches its Glass Transition Temperature (Tg), then flows. That structure is why ABS cools with controlled, predictable contraction.

ABS also resists warping because it does not “snap” into a crystal lattice during cooling. That reduces internal stress, keeps corners flatter, and stabilizes dimensions across typical processing windows. Expect shrinkage rates around 0.4–0.7% in molded parts, depending on grade and wall thickness.

Nylon is semi-crystalline. Its polymer chains form organized regions as the material cools. Those crystalline zones lock in density and strength, which is why nylon delivers higher structural performance. The same organization also drives higher shrinkage because the material packs tighter as crystals form.

Do not ignore this. Shrinkage rates for common nylon grades often land around 1.0–2.0%, with nylon 6/6 frequently near 1.5%. That difference directly affects fit, flatness, and tolerance stacks in production.

Impact Resistance vs Structural Strength

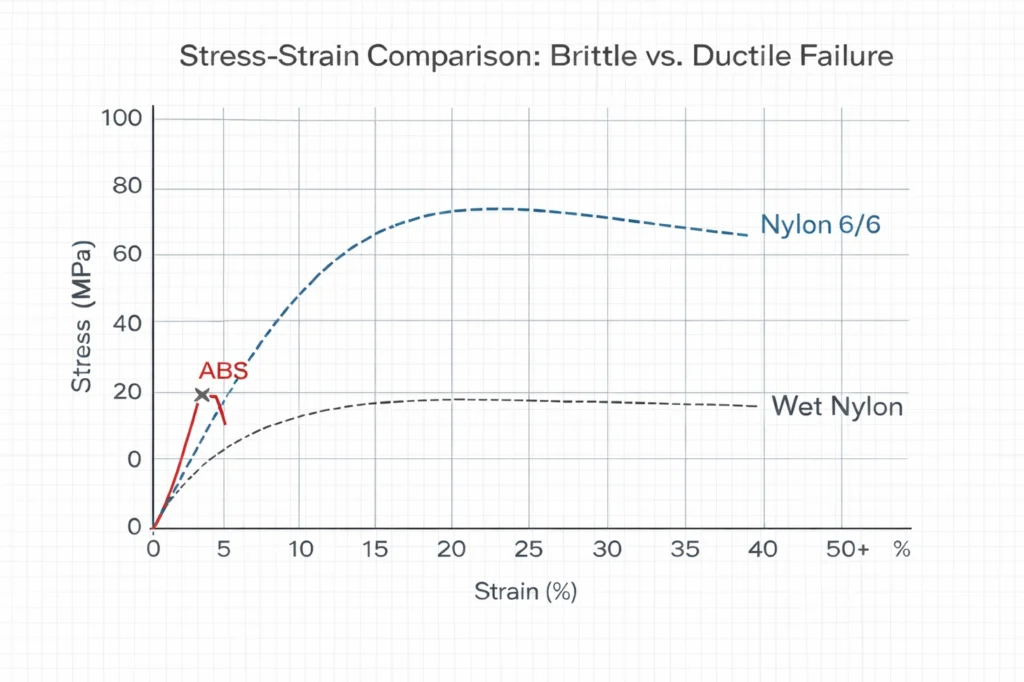

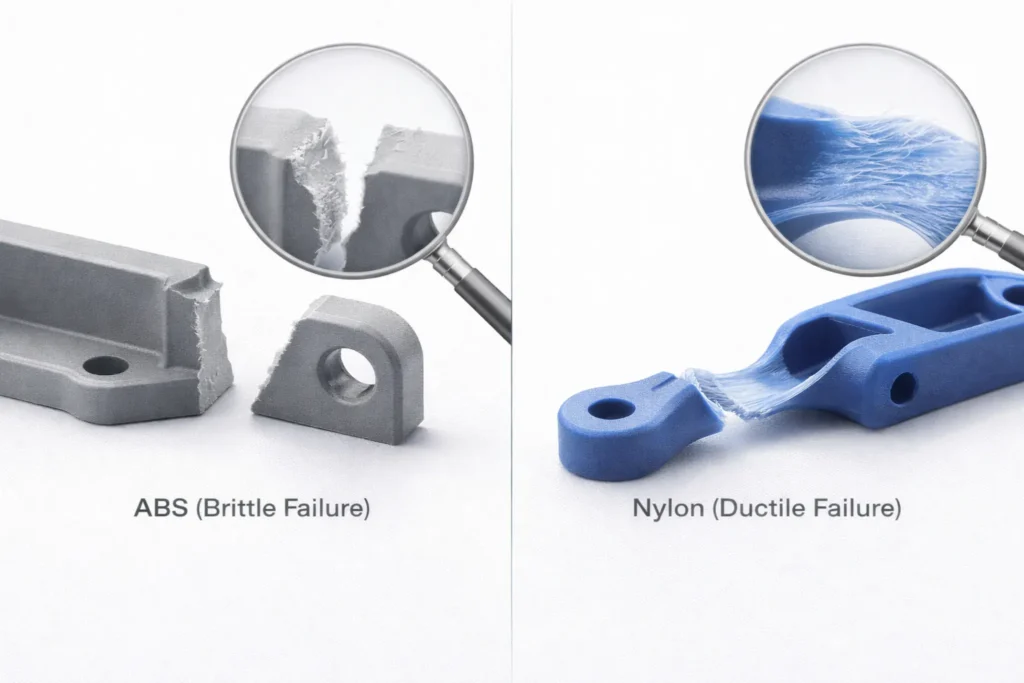

Do not confuse stiffness with strength. ABS is “hard” in the practical sense: it is stiff, impact resistant at room temperature, and holds shape until it hits a failure limit. When ABS exceeds that limit, it can show brittle failure with cracking, especially near stress concentrators or at low temperatures.

Nylon is “tough.” It combines tensile strength with ductility, so it absorbs energy by deforming rather than cracking. ABS will shatter under a hammer blow it can’t absorb; nylon will likely dent or deform, then recover closer to its original state if the stress stays below its yield and creep thresholds.

This is why nylon wins in hinges, clips, gears, and cyclic loading. Its crystalline structure supports fatigue resistance and improved energy absorption.

ABS wins when you need rigid geometry and repeatable parts near Tg-driven softening behavior, not crystal-driven contraction.

Strength, Toughness, and Load Handling

Tensile Strength vs Real-World Stress

Use tensile strength as a benchmark, not a guarantee. Nylon 6/6 typically delivers 75–85 MPa, while ABS usually sits around 35–45 MPa. Nylon looks like the clear winner on paper because its semi-crystalline structure carries load efficiently and supports higher elongation before fracture.

Now apply the real-world correction: nylon does not stay “dry.” As it approaches equilibrium moisture content, absorbed water plasticizes the polymer chains and reduces stiffness and yield behavior. Expect strength to drop by 30–50% in humid service unless you control conditioning and environment.

Treat this as a safety warning: a nylon part that meets spec in the lab can fall below your design margin in the field.

Design your parts for this moisture-driven shift. Account for the reduction in Elastic Modulus and the movement of the Yield Point when you select wall thickness, ribbing, and fastener loads. If you need consistent clamp force, stable gear mesh, or tight tolerance alignment, ABS often wins despite lower tensile numbers.

Nylon still wins for gears and wear parts because it handles cyclic stress, offers lower coefficient of friction, and behaves closer to self-lubricating under load.

Do not treat “stronger” as “more reliable.” Nylon’s strength depends on humidity, temperature, and conditioning. ABS stays more stable in dry indoor environments because it does not absorb water at the same level, so its mechanical response stays predictable.

Creep Resistance Under Continuous Load

Creep is deformation under constant stress over time. It is not a sudden failure mode. It shows up as slow bending, stretching, or loss of preload that creates Dimensional Drift months after launch.

Nylon resists impact and short bursts well, but it can creep under sustained tension or bending, especially when moisture and heat accelerate chain mobility. If you load nylon near its Yield Point, it will relax and shift geometry over long service intervals. Design with lower sustained stress, larger cross-sections, and realistic humidity assumptions.

ABS resists creep better in dry environments because its amorphous structure stays dimensionally stable under steady load at moderate temperatures. Do not push it into heat. As ABS approaches Tg-driven softening, creep accelerates and failure arrives faster than you expect.

Use nylon when load and wear dominate; use ABS when long-term geometry control dominates.

Heat Resistance & Dimensional Stability

Heat Deflection Temperature (HDT) Explained

HDT is your failure point for load-bearing geometry. It marks the temperature where a part stops acting like a structural component and starts behaving like a noodle under stress.

ABS typically deflects around 90–105°C under standard HDT test loads, depending on grade and reinforcement. Treat this as the upper boundary for parts that must hold shape under clamp force, screw bosses, or continuous bending. Above that range, ABS loses stiffness fast because it approaches Tg-driven softening.

Nylon 6/6 pushes the ceiling higher, but only if you control grade and condition. Unfilled nylon can soften earlier than buyers expect, especially when moisture reduces modulus. Dry or glass-filled nylon 6/6 can hold shape up to 180–200°C, which is why it shows up in under-hood and high-load wear applications. Do not assume every nylon part survives at those temperatures. Confirm the exact grade, reinforcement, and moisture state.

Warping, Softening, and Long-Term Heat Exposure

Heat does not only bend parts; it ages them. ABS experiences oxidative degradation under repeated heat cycling, which drives embrittlement over time. You may see cracks at ribs, snap features, or around fasteners even if the part never exceeds its HDT.

Nylon tolerates higher service temperature better, but it can yellow and oxidize without heat-stabilized grades. Specify heat stabilizers when the part sees sustained heat, engine-bay airflow, or long duty cycles near the upper service range.

Dimensional stability depends on both heat and expansion behavior. Compare the Coefficient of Thermal Expansion (CTE) and how the part is constrained. ABS expands more predictably. Nylon changes dimensions from CTE and moisture, which complicates tolerance control in assemblies.

Do not ignore warping during manufacturing. Nylon’s semi-crystalline shrink behavior makes molding and 3D printing more sensitive to cooling rates, part thickness changes, and bed or mold temperatures. ABS processes with less warp because it cools more uniformly.

Use nylon when heat and load demand it, but design the process to manage warpage and post-cooling distortion.

Moisture, Chemicals, and Environmental Resistance

Moisture Absorption and Its Impact on Nylon

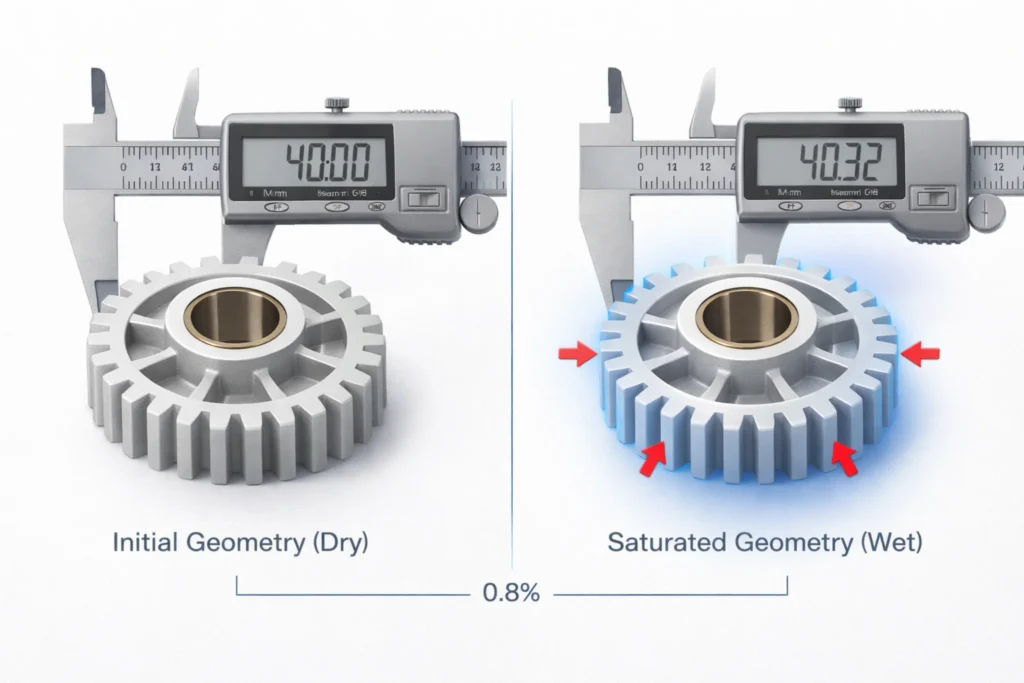

Nylon is hygroscopic. It absorbs moisture from air and liquid water, then changes dimensions and mechanical behavior. Nylon 6 and 6/6 can absorb up to 8% water by weight at saturation. That uptake typically drives 0.5–0.8% dimensional swell, which destroys tight fits and shifts load paths.

Treat moisture as a design input, not an afterthought. When nylon absorbs water, it gains ductility but loses stiffness and strength. That shift changes gear backlash, hinge alignment, and clamp load. It also increases the risk of Dimensional Drift across seasons and locations.

Mitigate it with controlled conditioning. Condition parts before final inspection and assembly so they reach equilibrium and stop moving later. Use a pre-soak or controlled humidity step that matches the real service environment. Lock the process: define conditioning time, temperature, and storage method.

Do not assemble dry nylon parts into tight-tolerance systems unless you accept growth later. If the assembly must hold alignment, specify stabilized grades, increase clearances, or switch to ABS when moisture stability matters more than peak mechanical performance.

Chemical Resistance and Surface Stability of ABS

ABS performs well in many household environments, but certain solvents attack it quickly. Nylon tolerates oils, greases, and fuels better, which pushes it into automotive and industrial use. ABS fits consumer and indoor applications where exposure stays mild and predictable.

Use this hazard list during material approval:

- Avoid acetone with ABS

- Avoid ketones with ABS

- Avoid esters with ABS

- Avoid phenols with nylon

- Avoid strong acids with nylon

Nylon generally handles oils, greases, diesel, and many fuels well, making it the stronger choice for shop-floor exposure and under-hood components.

Keep ABS away from nail polish remover, paint thinners, aggressive degreasers, and solvent-based cleaners if you want surface stability and long-term appearance.

UV Resistance & outdoor Aging (ABS vs Nylon vs ASA)

Both ABS and nylon struggle outdoors without protection. ABS tends to yellow and chalk under UV, which reduces surface integrity and impact resistance over time. Nylon can become brittle as UV breaks polymer chains, especially in thin sections and stressed features.

If you want ABS-like processing and surface quality but need long outdoor service, use ASA (Acrylonitrile Styrene Acrylate). ASA keeps the dimensional predictability and finish advantage, but it delivers far better UV stability for extended exposure.

For parts that must survive sun, rain, and temperature cycles for years, ASA is often the practical “third-way” solution when ABS plastic vs nylon both introduce unacceptable outdoor aging risk.

Manufacturing & Processing Considerations

Injection Molding Behavior

ABS typically runs faster on the press. It is amorphous, so it does not need to crystallize before ejection. That shortens cycle time and reduces warp risk across a wider processing window. Most ABS grades process around 230–260°C, with mold temperatures commonly set to keep surfaces clean and stable.

Nylon demands tighter discipline. Verify moisture before you start. Dry nylon with a desiccant system to <0.2% moisture or you will get splay (silver streaks), voids, and structural weakness. Moisture flashes into steam in the barrel and destroys surface quality and strength.

Dry the material for 4–8 hours at the supplier-recommended temperature, then keep it sealed until it enters the hopper. Run nylon at higher melt temperatures often 250–290°C depending on grade and control mold temperature to manage crystallization and shrink. Expect higher shrinkage and more sensitivity to thick-to-thin transitions than ABS.

CNC Machining & Tolerance Holding

ABS machines cleanly. It chips well, holds edges, and leaves a predictable finish. Use it when you need cosmetic surfaces, sharp features, and reliable tolerance holding without post-machining movement.

Nylon behaves gummy. It can smear, wrap around a drill bit, and melt if you push feed too hard or let heat build. Ensure sharp tooling and avoid dull edges that generate friction.

Use high spindle speeds and low feeds to reduce heat and prevent surface tearing. Clear chips aggressively to avoid re-cutting and localized melting.

Account for post-machining movement. Nylon can relax and shift dimensions after machining, especially if moisture content changes. Measure after conditioning if the part must meet tight specs.

3D Printing (ABS vs Nylon Filaments)

ABS prints well when you control the thermal environment. Ensure a heated chamber at 60°C+ and a stable heated bed to minimize warp and layer splitting. Expect strong parts, good surface finish, and predictable dimensions if you prevent rapid cooling.

Nylon prints as a functional material, not a cosmetic one. Ensure a heated bed at 100°C+ and dry the filament before printing to prevent bubbling and weak layers. Many nylon blends also demand enclosure heat to control warp. If you print reinforced nylon, use a hardened steel nozzle to resist abrasive fillers.

Reinforced Variants (Glass filled and Carbon Fiber Nylon)

Use carbon fiber (CF) nylon when standard nylon feels too flexible or warps during cooling. CF reinforcement boosts stiffness, improves dimensional stability, and reduces warp, which directly addresses nylon’s biggest processing weakness. It also increases abrasion, so verify nozzle and extruder wear.

Environmental Health & VOC Emissions (ABS vs Nylon)

Treat emissions as a compliance issue. ABS releases styrene fumes during printing and overheating, which acts as a known respiratory irritant. Ensure active ventilation, enclosure filtration, and workplace exposure controls. Do not print ABS in an unventilated room.

Nylon can also emit VOCs, especially at high temperatures, so apply the same filtration and airflow standards for shop safety.

Durability, Wear, and Failure Patterns

Abrasion, Fatigue, and Surface Wear

Nylon dominates wear applications because it combines low coefficient of friction with strong fatigue life. It tolerates sliding contact, rolling contact, and repeated flex without cracking. In real assemblies, that matters more than peak tensile strength.

Treat nylon as a self-lubricating option for gears, bearings, bushings, cam followers, and sliding guides. It can run against steel and many plastics with reduced noise and reduced wear when loads stay within design limits. It also handles cyclic bending well, often surviving millions of flex cycles when you control stress concentration and moisture state.

ABS does not compete here. Use it for rigid housings, covers, and fixtures where surfaces stay mostly static. ABS can survive impact, but it will wear faster under sliding contact and loses performance when friction heat builds.

Do not spec ABS for gear teeth, bushings, or high-cycle flex parts.

Common Failure Modes (Cracking vs Deformation)

Use failure signatures to diagnose material choice and root cause. ABS tends to fail suddenly through brittle fracture once cracks start.

Nylon usually fails through plastic deformation, giving warning before total failure.

Primary failure signatures:

- ABS: brittle fracture, cracking, shattering, sharp crack lines

- Nylon: yielding, stretching, bending, whitening at stress zones, gradual loss of stiffness

If you see cracks, the material was likely ABS or the nylon was UV damaged and embrittled.

If you see deformation with the part still intact, nylon likely carried the load but crept, absorbed moisture, or exceeded its yield threshold.

Use these signatures to decide whether you need higher ductility, better wear properties, or tighter dimensional control in the next design iteration.

Cost, Availability, and Lifecycle Value

Raw Material Cost vs Processing Cost

ABS usually wins on raw material cost per kg and broad availability. Buyers can source consistent grades quickly, and processors run it with fewer prep steps. That does not mean ABS is cheaper in production.

Track Total Cost of Ownership across the full process. Nylon often demands desiccant drying, controlled storage, and conditioning steps that add energy and labor. Nylon also tends to run longer cycles in molding because crystallization and shrink control require tighter processing windows. Those costs compound across high-volume programs.

Price spreads widen as you move up the nylon ladder. Standard nylon 6 or 6/6 may sit close to engineering ABS grades, but high-performance polyamides change the economics.

Nylon 11 or 12 can cost 2x–4x more than standard ABS, especially in filament and specialty molding grades. Only approve those materials when the environment or durability requirement forces the decision.

Replacement Frequency and Long-Term ROI

Short-term cost is irrelevant if the part fails in service. Run a simple replacement model. If an ABS component fails every 6 months while a nylon component survives 3 years, nylon wins even at a higher unit price because labor, downtime, and warranty claims dominate the budget.

Allocate budget to nylon for high-wear areas to reduce warranty returns.

Use ABS where loads stay moderate, environments stay dry, and failure risk remains low.

Treat nylon as the reliability material when friction, cyclic stress, or elevated heat drives real-world failure.

Best Material by Application (Decision Section)

Automotive & Mechanical Parts

Use nylon when heat, fluids, and vibration dominate.

Use ABS when the part is visible, handled, and dimensionally controlled inside the cabin.

- Use nylon for engine-bay covers, intake manifolds, and fuel lines

- Use nylon for brackets near heat sources, clips under load, and fluid-exposed components

- Use ABS for dashboard trims, air vents, and center consoles

- Use ABS for interior housings where cosmetics, rigidity, and tight fit matter

Verify the nylon grade. Specify heat-stabilized or glass-filled variants for elevated service temperature and creep control.

Keep ABS away from hot zones and solvent exposure.

Consumer Products & Enclosures

ABS wins when finish and assembly speed drive value. It delivers a consistent hand-feel, clean surfaces, and reliable snap-fit performance without moisture-driven drift.

- Use ABS for electronics housings, remote controls, and toys

- Use ABS for appliance panels, cosmetic covers, and clip-together assemblies

- Use nylon only when the product includes moving joints, wear interfaces, or repeated flexing

If the part must hold tight tolerances across seasons, ABS reduces dimensional risk and lowers inspection fallout.

Gears, Bearings, and Moving Components

Choose nylon for motion. Do not use ABS for power-transmission gears.

- Use nylon for gears, bearings, bushings, and sliding rails

- Use nylon for hinges, latches, and high-cycle flex parts

- Avoid ABS for gear teeth, wear pads, or any component that sees continuous friction

Friction generates localized heat spikes at contact points.

ABS softens as it approaches Tg and the teeth deform, strip, or crack.

Nylon’s semi-crystalline structure and lower coefficient of friction handle those heat spikes and distribute stress more effectively.

For higher stiffness and reduced warping, specify CF nylon where the design demands tighter geometry under load.

Final Recommendation (ABS Plastic or Nylon)?

Make the decision based on your primary constraint. If the part must carry load, survive wear, or tolerate heat, choose nylon.

If the part must hold tight dimensions, stay flat, and deliver a clean finish at low risk, choose ABS.

Do not try to force ABS into moving or high-heat systems.

Do not use nylon in tight-tolerance assemblies unless you control moisture and conditioning.

Use nylon when failure costs money. Use ABS when precision and repeatability protect your assembly yield.

Decision Summary Table by Use Case

| Goal | Winner |

| Peak Strength | Nylon |

| Precision/Low Warp | ABS |

| Wear/Gears | Nylon |

| Lowest Cost | ABS |

| Heat Resistance | Nylon (Glass Filled) |

Key Takeaways (Executive Summary)

- Choose nylon when load, wear, and fatigue life drive performance. It offers a low coefficient of friction, long fatigue endurance, and self-lubricating behavior for moving parts.

- Manage nylon’s hygroscopy or it will move and soften. Nylon can absorb up to 8% water and swell 0.5–0.8%, reducing strength and shifting tolerances.

- Choose ABS when precision, low warp, and cosmetic finish matter. Its amorphous structure holds geometry with shrinkage around 0.4–0.7%.

- Watch ABS for brittle failure and heat aging. ABS can crack or shatter under overload and becomes more brittle under long-term heat cycling.

- If outdoor UV matters, switch to ASA. It keeps ABS-like stability with superior weathering for long service life.

FAQs

Is Nylon stronger than ABS?

Yes in tensile strength, but ABS is stiffer in dry service. Nylon 6/6 typically reaches 75–85 MPa versus ABS at 35–45 MPa, but nylon strength can drop 30–50% near equilibrium moisture content.

Can I use ABS for outdoor applications?

Not recommended. ABS yellows, chalks, and degrades under UV, so use ASA when you need ABS-like processing with long-term outdoor stability.

Why do my Nylon parts change size?

Nylon is hygroscopic and absorbs water into its polymer chains. Nylon 6 and 6/6 can absorb up to 8% water at saturation, causing 0.5–0.8% dimensional swell that shifts tolerances and reduces stiffness.

Which is better for 3D printing gears?

Nylon, especially carbon-fiber reinforced variants. ABS softens from friction heat at contact points and deforms gear teeth, while nylon handles localized heat spikes, fatigue, and wear with a lower coefficient of friction.

Is ABS more toxic than Nylon when heated?

Yes from a workplace exposure standpoint. ABS can release styrene fumes, a known respiratory irritant, so ensure active ventilation and HEPA/carbon filtration to meet shop safety expectations.