Can You Heat Press Nylon? Safe Temperatures, Materials That Work, and When to Avoid It

Heat pressing nylon is a high-risk technical process that requires a strict thermal protocol to prevent irreversible fabric scorching.

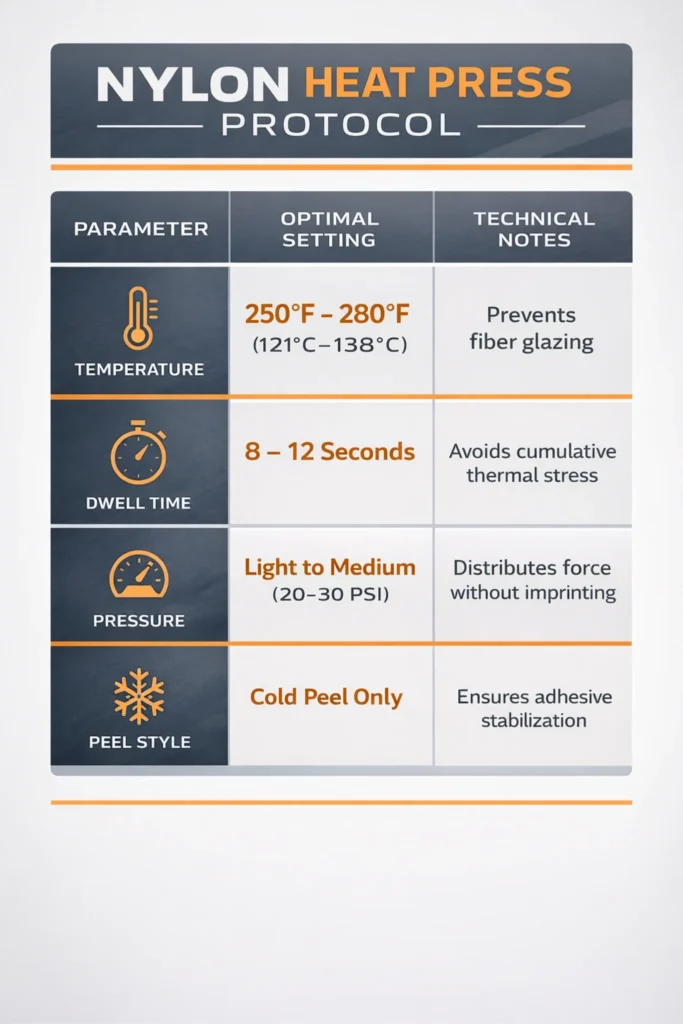

Success is contingent upon utilizing low-melt adhesives and maintaining temperatures between 250°F and 280°F.

This guide outlines the operational thresholds and material compatibility required to achieve a permanent bond on synthetic fibers without compromising the garment’s structural integrity.

Quick Answer — Can Nylon Be Heat Pressed Safely?

The Short Verdict (When It Works vs When It Fails)

Nylon can be heat pressed successfully if the operator prioritizes thermal accuracy over speed. Unlike standard polyester, nylon requires specialized nylon-rated HTV or DTF transfers with low-temperature powders.

Failure occurs most frequently when standard 300°F+ settings are used, leading to localized fiber melting or adhesive rejection.

| Conditions for Success | Causes of Failure |

| 250°F–280°F (121°C–138°C) | Temperatures >300°F (Scorching) |

| 8–12 Second Dwell Time | Excessive dwell (Fabric Deformation) |

| Teflon/Protective Barrier | Direct Platen Contact (Shine Marks) |

| Water-Drop Test (DWR Check) | Unremoved Waterproof Coatings (Peeling) |

Why Nylon Is Heat-Sensitive Compared to Other Fabrics

Nylon is a synthetic thermoplastic polymer, meaning it transitions from a solid to a semi-fluid state at significantly lower temperatures than natural fibers. While cotton fibers char at high heat, nylon fibers constrict and glaze, resulting in permanent “shine marks.”

Because nylon has higher moisture sensitivity and a lower glass transition temperature than polyester, it is less tolerant of thermal fluctuations during the press cycle.

Why Nylon Is Difficult to Heat Press (Material Reality)

Melting Point vs Heat Press Temperatures

Nylon exhibits a narrow margin between adhesive activation and thermal deformation. While industrial grades like Nylon 6 possess a melting point of approximately 428°F (220°C), the fiber begins to lose structural integrity and “glaze” far below this threshold.

To prevent fiber constriction and warping, the safe operational ceiling for nylon is typically capped at 285°F (140°C). Exceeding this range causes the thermoplastic fibers to flatten under pressure, resulting in permanent “shine marks” that cannot be reversed by washing or steaming.

Coatings, Weaves, and Why “Nylon” Is Not One Material

The primary obstacle in nylon decoration is not the fiber itself, but the Durable Water Repellent (DWR) coatings applied to rainwear and tactical gear. These chemical finishes lower the substrate surface tension, intentionally preventing liquids and adhesives from penetrating the weave.

Standard heat-transfer adhesives require “wet-out”—the ability of the glue to flow into the fabric fibers to create a mechanical bond.

DWR-treated nylon acts as a chemical barrier, causing adhesive rejection and post-wash peeling. In these instances, a chemical primer or specialized nylon-bond adhesive is mandatory to bypass the coating’s repellent properties.

Safe Heat Press Settings for Nylon (Critical Section)

Recommended Temperature Range (°F & °C)

The operational “Golden Zone” for nylon application is 250°F to 280°F (121°C–138°C). This specific range activates the chemical cross-linking in nylon-grade adhesives while remaining below the fiber’s thermal deformation point.

If substrate moisture is detected, perform a 2–3 second pre-press using a protective barrier. All thermal adjustments must be validated via a test-press on an inconspicuous seam, as fabric density and denier significantly impact heat absorption rates.

Pressure and Dwell Time Limits

Configure equipment for light to medium pressure (20–30 PSI) with a primary dwell time of 8–12 seconds. On nylon, extended exposure is a higher risk factor than temperature; the fabric suffers from cumulative thermal stress the longer the platen remains engaged.

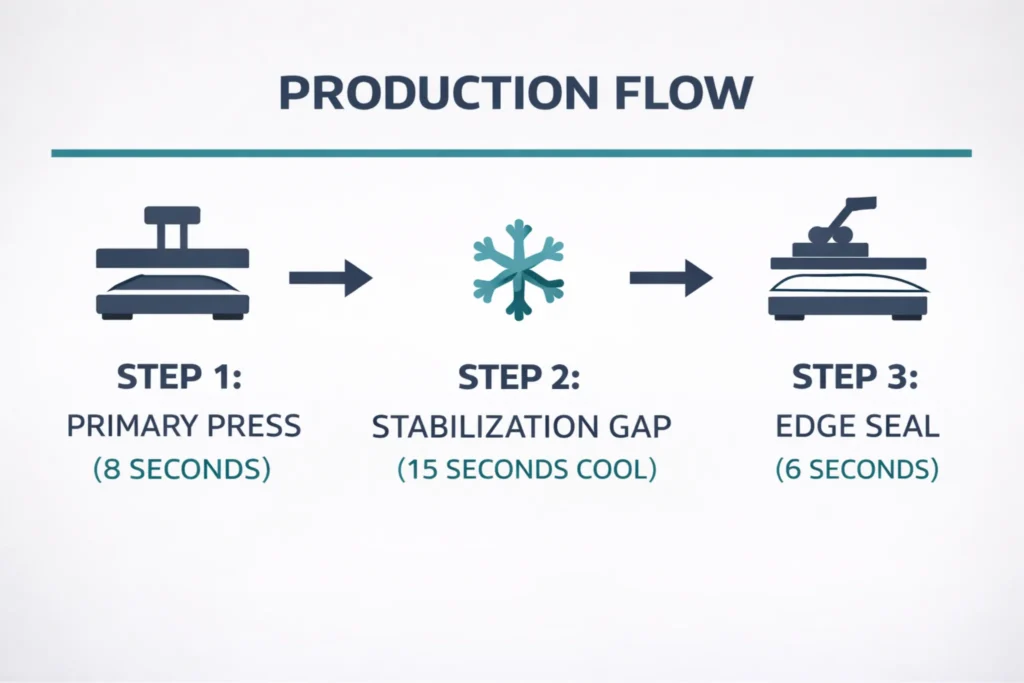

If initial adhesion is insufficient, do not increase dwell time beyond the 12-second ceiling. Instead, utilize a dual-press cycle: press for 8 seconds, allow a 15-second cooling interval, then apply a secondary 6-second press. This prevents fiber collapse while ensuring the adhesive reaches the required viscosity for fiber penetration.

Why Over-Pressing Destroys Nylon Instantly

Excessive pressure results in mechanical crushing of the synthetic weave, creating a permanent “heat ring” or glossy glaze. This occurs most frequently at the perimeter of the heat platen or where seams create localized high-pressure zones.

Pneumatic presses present a higher risk of imprinting texture into the substrate. To mitigate this, reduce pressure settings and utilize a heat press pillow to distribute force evenly across uneven surfaces, ensuring the platen does not make direct, high-force contact with the garment edges.

Best Transfer Types That Actually Work on Nylon

Heat Transfer Vinyl (HTV) for Nylon

Standard polyurethane (PU) films lack the aggressive bonding agents required for slick, synthetic fibers. Success requires nylon-specific HTV, such as Siser EasyWeed Extra or Stahls’ Gorilla Grip II, which feature a specialized extra-adhesive chemistry.

These formulations are engineered to bond with low-energy surfaces where standard adhesives fail to “bite.” This adhesive tuning ensures the film remains anchored even as the nylon substrate expands and contracts during thermal shifts or physical wear.

DTF Transfers on Nylon — What to Watch For

Direct-to-Film (DTF) transfers are compatible with nylon provided they utilize a low-melt TPU powder. Application should be restricted to 275°F–285°F (135°C–140°C) with light pressure to mitigate fiber glazing.

A critical operational step is the secondary seal press. Performing a 5-second post-peel press through a protective sheet ensures the adhesive layer achieves full fiber encapsulation. This step is non-negotiable for achieving industrial-grade wash durability on nylon.

Screen Print Transfers vs Sublimation (Why Sublimation Fails)

Low-temperature screen print transfers are highly effective on nylon due to their high opacity and elasticity. Because they activate at lower thermal thresholds, they minimize the risk of substrate scorch while providing a “soft hand” finish.

In contrast, Sublimation is fundamentally incompatible with nylon. Sublimation requires temperatures of 380°F–400°F to facilitate gas-dye conversion—a range that exceeds nylon’s thermoplastic transition point. Attempting sublimation on nylon results in immediate fabric warping, melting, or permanent “burn-in” before the ink can transfer.

Nylon Types That Are Safe vs Unsafe to Heat Press

100% Nylon vs Blended Nylon Fabrics

100% nylon is a manageable substrate when applying low-temperature protocols. However, the introduction of elastic fibers like Spandex or Elastane alters the operational requirements.

Blends introduce dynamic stress on the bond. Stretch-rated transfers (e.g., highly flexible PU HTV or specific DTF films) are mandatory to prevent bond fracture and lifting during garment flexion.

Ripstop, Coated, and Waterproof Nylon (High Risk)

Substrates with high risk of adhesive failure and surface damage include:

- Ripstop: The reinforced “box weave” creates inherent pressure gaps during pressing.

- Waterproof Jackets: Utilize DWR (Durable Water Repellent) coatings that actively repel adhesives.

- Tactical Gear/Bags: Often feature heavy denier Cordura, which demands specific, high-bond adhesives.

- Umbrellas/Canopies: Ultra-thin, coated substrates are prone to instant thermal deformation.

When Manufacturer Labels Override General Rules

The manufacturer’s care instructions serve as the primary compliance directive. The presence of a “Do Not Iron” symbol indicates a high probability of chemical treatment or an extremely low thermal tolerance.

In such scenarios, thermal application is strongly discouraged. Alternatives such as mechanical fastening (sew-on patches) or embroidery mitigate all thermal risks to the garment.

Step-by-Step: How to Heat Press Nylon Without Damage

Pre-Press Setup (Testing Before Production)

Validate the substrate’s adhesive receptivity using the Water Drop Test. Apply 2 drops of water to the target area; if the water beads, a DWR coating is present, necessitating a specialized nylon-bond transfer.

Conduct a thermal limit test on an internal hem. This confirms the fabric’s reaction to the intended temperature, allowing you to detect fiber glazing or warping before beginning the production run.

Using Protective Sheets and Lower Platens

A thermal barrier (Teflon or parchment) is mandatory to prevent direct platen-to-fiber contact. This shielding mitigates the risk of localized melting and high-gloss press marks.

Utilize heat press pillows for any garment containing zippers, seams, or buttons. Elevating the print area ensures uniform pressure distribution, preventing the “edge rings” caused by the platen making contact with thick seams.

Cooling, Peeling, and Post-Press Checks

Adhere strictly to a Cold Peel protocol. Most nylon-rated adhesives require a cooling phase to achieve structural stabilization before the carrier sheet is removed.

Perform a post-press for 3–5 seconds to seal the transfer edges. Validate the bond by performing a lateral tension test (gentle stretching); if delamination occurs, re-press using the dual-cycle method rather than increasing the temperature.

Common Failures and How to Avoid Them

Melting, Scorching, and Shine Marks

Thermal degradation manifests as fiber constriction, resulting in ripples, hardened patches, or a high-gloss “glaze.” Scorching is identified by a yellowed discoloration and localized stiffness in the weave, typically occurring at high-pressure contact points.

These marks are caused by the refractive properties of crushed fibers. To mitigate this, lower the temperature by 10-degree increments and utilize a silicone foam pad to soften the impact of the heat platen.

Adhesion Failure After Washing

Post-wash delamination is primarily caused by chemical interference from DWR coatings. While the adhesive may achieve an initial mechanical “tack,” the water-repellent barrier prevents it from penetrating the fiber.

This creates a superficial bond that fails under the mechanical stress of the wash cycle. Ensure the use of nylon-specific adhesives and perform a pre-treatment solvent wipe if the water-drop test indicates high surface tension.

Why “It Looked Fine at First” Is a Red Flag

Initial visual success can mask latent adhesion failure. This occurs when the adhesive has not reached its necessary viscosity for fiber encapsulation, resulting in a bond that brittle-fractures over time.

Validate the application by performing a Lateral Flex Test: once fully cooled, gently stretch the substrate. Any micro-fracturing at the perimeter indicates an insufficient bond, requiring an adjustment in dwell time or adhesive type before continuing production.

When You Should NOT Heat Press Nylon (Alternatives)

Situations Where Heat Pressing Nylon Is a Bad Idea

Thermal application is contraindicated for low-denier sheer nylon, where the risk of instant fiber distortion is nearly 100%.

Avoid heat pressing on multi-layer technical shells or garments with integrated membrane systems (e.g., Gore-Tex), as high temperatures can delaminate the internal waterproof barrier.

Furthermore, items featuring reflective safety laminates or factory heat-sealed seams should not be subjected to secondary heat cycles. The application temperature required for the transfer often exceeds the structural melting point of the garment’s existing seam tape, leading to structural failure.

Better Alternatives (Sew-On Patches, Adhesives, Embroidery)

When the substrate’s thermal sensitivity or chemical coating prohibits heat pressing, utilize one of the following mechanical or low-heat fastening methods:

- Sew-on Patches: The gold standard for DWR-coated nylon; provides a permanent mechanical bond regardless of surface tension.

- Direct Embroidery: Offers high-durability branding for heavy-denier fabrics like Cordura without risking surface glaze.

- Velcro/Hook-and-Loop: Ideal for tactical gear and flight jackets; allows for interchangeable branding with zero thermal exposure.

- Pressure-Sensitive Adhesives (PSA): Specialized “peel-and-stick” emblems designed for high-energy surfaces where heat is not an option.

Final Recommendation — Is Heat Pressing Nylon Worth It?

Who Should Do It and Who Should Avoid It

Heat pressing nylon is a viable production method for professional decorators equipped with digital temperature controls and specialized nylon-rated adhesives. However, for high-value waterproof gear or sheer luxury garments, the risk of permanent thermal deformation often outweighs the benefits. In these cases, mechanical fastening remains the most reliable solution for long-term durability.

FAQs

What temperature will melt nylon?

Pure Nylon 6 begins to melt at 428°F (220°C), but permanent surface glazing and fiber shrinkage occur as low as 300°F (149°C).

Can you heat press nylon backpacks or jackets?

Yes, provided you utilize heat press pillows to navigate seams and internal plastic linings. Maintain a temperature ceiling of 280°F to avoid melting internal coatings.

Does DTF stick to nylon?

DTF is compatible only if a low-melt TPU powder is used. Standard powders require temperatures that typically exceed the safety threshold of nylon fibers.

Is nylon heat-press safe long term?

Yes. When bonded with a nylon-specific adhesive at the correct dwell time, the transfer will maintain integrity throughout the standard life cycle of the garment.