Glass Filled Nylon: Grades, Performance Trade-Offs, and When It Actually Makes Sense

Glass Filled Nylon is not a “materials theory” topic—it’s a material selection decision where the wrong choice can trigger cracking, warpage, and in-field failure.

In this post, I’ll give you direct, engineering-level clarity on when Glass Filled Nylon actually makes sense—and when it only increases cost and risk.

We will evaluate the practical trade-offs across GF20, GF30, and GF40 grades: stiffness versus impact strength, heat resistance versus moisture sensitivity, and dimensional stability versus surface quality. You’ll get decision rules tied to load, temperature, and tolerance targets, so you can select the right grade without guessing.

The goal is simple: justify the added cost with measurable performance gains, and reduce the failure risk that comes from using the wrong grade in the wrong environment.

Quick Verdict (Should You Use Glass Filled Nylon or Not)?

Use glass filled nylon when your part must hold shape under load, maintain stiffness at elevated temperature, and replace metal without adding bulk.

It is the right call when your design is limited by deflection, creep, or mounting stability, not when you just want “strong plastic.”

If you specify the wrong grade or ignore moisture and notch sensitivity, the failure mode is usually cracking or warpage, and the cost premium becomes unjustified.

Treat this as a rules-based selection: match grade, geometry, and environment, then verify with testing not assumptions.

- Use glass filled nylon when continuous service temperature is ≥120°C, and you need low deflection under load.

- When you must control creep for assemblies with screws, clips, or bearing surfaces under constant stress.

- Avoid it when impact, snap-fit flexibility, or drop performance is the priority (high stiffness increases brittle fracture risk).

- Avoid it when you cannot manage moisture-driven dimensional change or surface finish constraints tighter than ±0.2% without validation.

What Changes When Nylon Is Glass-Filled (Performance Reality)

Strength vs Brittleness (The Core Trade-Off)

Glass fiber turns Nylon from “bend-first” behavior into “hold-shape” behavior.

Your part will carry higher loads with less deformation, so designers often push thinner walls or higher clamp forces. That’s where the trap starts. The same reinforcement that boosts strength also removes the material’s ability to absorb shock.

Instead of flexing and recovering, the part concentrates stress at corners, ribs, threads, and screw bosses then snaps. If you over-design a stiff grade into a part that needs energy absorption, you create a brittle failure machine.

Treat Glass re-inforced Nylon like a material that dislikes sharp geometry. Tight radii, thin hinges, and aggressive snap-fits are common fracture starters.

If your design depends on “give,” don’t try to force it with more glass. Higher glass content increases stiffness, but it also increases the risk of brittle fracture, especially in dry-as-molded parts and cold conditions.

Stiffness, Heat Resistance, and Dimensional Stability

The real win is stiffness retention at temperature. Glass limits how much Nylon softens as it heats, so the part holds alignment under load instead of creeping out of spec.That is why Glass Filled Nylon is used for brackets, housings, motor mounts, and structural frames.

Heat deflection improves because the fibers carry load when the polymer matrix is getting softer. That does not mean the part is “tough” at heat it means it stays stiff longer.

Dimensional stability also improves because glass reduces shrink variability and lowers expansion compared to unfilled Nylon.But stability has a condition: you still must manage moisture uptake. Glass reduces movement, it does not delete it. If your tolerance stack requires tight fits, you must validate dimensions after conditioning, not just after molding.

Remember the rule: stiffness is resistance to bending; toughness is resistance to cracking. Glass increases the first, and can reduce the second.

Glass–Reinforced Nylon Grades Explained (GF20, GF30, GF40)

Glass Filled Nylon is Usually PA6 or PA66 – Why That Matters

“PA GF” is not one material, and treating it like a single spec is a selection mistake that shows up later as drift in dimensions, loss of clamp load, and premature creep.

In practice, you are usually choosing between PA6 GF and PA66 GF. That base polymer choice changes how the part behaves after moisture exposure, and how reliably it holds performance at temperature.

If you are building tight-tolerance assemblies, or anything that lives near heat sources, the PA6 vs PA66 decision is risk mitigation not a detail.

| Base polymer | Moisture absorption tendency | Heat resistance trend | When to choose / avoid |

| PA6 GF | Higher uptake → more dimensional shift and faster property drop | Lower vs PA66 | Choose for cost-sensitive parts with moderate heat and tolerances; avoid for tight fits, long-term load, and high humidity exposure |

| PA66 GF | Lower uptake → better stability and strength retention | Higher vs PA6 | Choose for under-hood, electrical enclosures, and sustained heat; avoid when cost is tight and thermal demand is moderate |

GF20: When Moderate Reinforcement Is Enough

Use GF20 when you need a meaningful stiffness upgrade but still want some “forgiveness” in assembly and impact.

This grade is the safer choice for parts with snap features, thin ribs, or designs that see occasional shock loads. You get better dimensional control than unfilled Nylon without pushing the part into brittle behavior.

GF20 also makes sense when your real constraint is deflection at room temperature not sustained heat or constant stress.

If your design has sharp corners or high stress concentration you can’t redesign, GF20 is often the best compromise because it reduces the brittle fracture tendency compared to higher glass grades.

GF30: The Industry Standard (And Why)

GF30 is the default when engineers need consistent stiffness, creep control, and stable assembly geometry under load.

It is the “standard” because it hits a practical balance: high reinforcement without becoming unmanageably brittle in most well-designed parts.

Use it for brackets, housings, covers, and structural frames where fastener torque, clamp load, and alignment retention matter.

GF30 is also where cost-to-performance typically justifies itself especially when replacing metal or reducing wall thickness.

The key condition: your geometry must respect stress concentration rules, or the added stiffness becomes a crack trigger at bosses, knit lines, and corners.

GF40+: High Stiffness, High Risk Applications

Use GF40+ only when your design is stiffness-limited at higher temperature, and you have controlled geometry and predictable loading.

This is not a “more is better” upgrade. GF40+ increases stiffness and reduces creep further, but the part becomes more notch-sensitive and less tolerant to abuse, impact, and assembly variation.

It is most appropriate for rigid frames, high-load mounts, and components where deformation is the failure mode not cracking.

If your application includes vibration + impact, uncertain fastener torque, or sharp transitions you cannot soften, GF40+ can fail suddenly via brittle fracture and turn a premium material into a reliability problem.

| Grade | Typical use | Failure risk | When to avoid |

| GF20 | Semi-structural parts, clips, moderate-load housings | Lower brittleness, but still stress-sensitive | Avoid when heat + constant load drives creep, or when stiffness is still insufficient |

| GF30 | Structural housings, brackets, frames, fastened assemblies | Crack initiation at bosses/corners if geometry is poor | Avoid for high-impact parts, flexible snap designs, or uncontrolled assembly torque |

| GF40+ | High-stiffness mounts, rigid frames, deformation-critical parts | High notch sensitivity → brittle fracture risk | Avoid for impact/vibration abuse, sharp geometry, thin sections, or variable torque conditions |

Critical Failure Risks Most Suppliers Don’t Explain

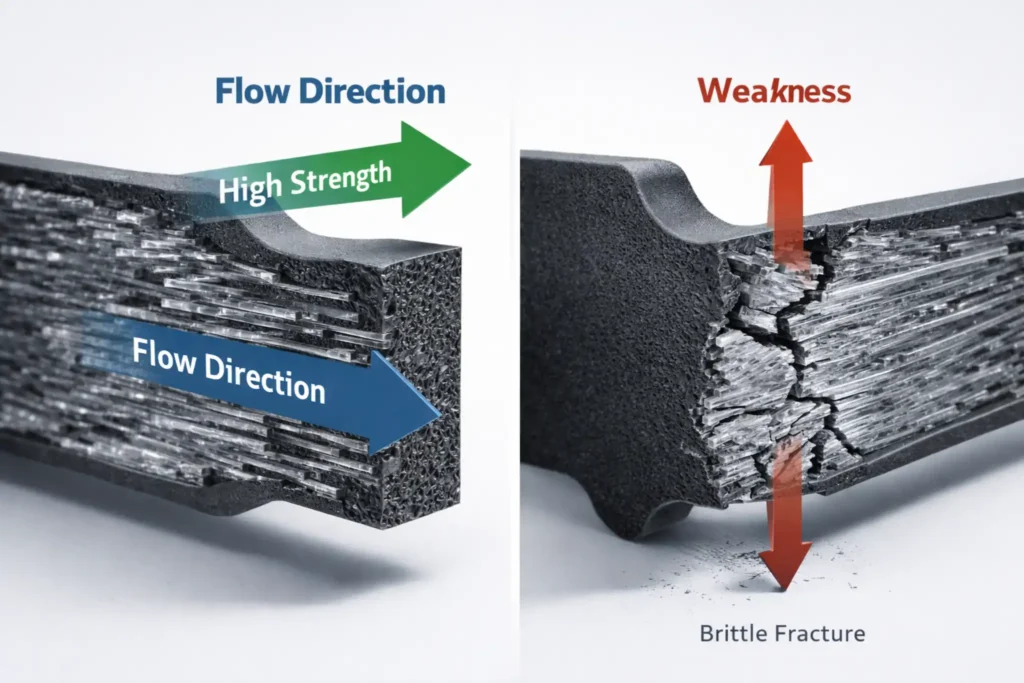

Fiber Orientation & Anisotropic Weakness

Glass fibers do not reinforce in all directions. During molding, fibers align with flow, so the part becomes strong and stiff in one direction and noticeably weaker across it.

In practice: the same part that survives high load along the flow path can split when the load is sideways.

If you ignore this, you will misread datasheets and overestimate safety margins.

The risk spikes at weld lines, around holes, and near sharp transitions where flow changes direction.

Treat “flow direction” like a design parameter, not a processing detail.

If your part carries bending, torque, or off-axis loads, you must validate strength across flow not only along it or the failure will look random but it is fully predictable.

Creep, Fatigue, and Long-Term Load Behavior

Glass Filled Nylon improves creep resistance, but it does not eliminate it. Under constant stress clamp load from screws, spring force, or continuous bending the polymer matrix slowly relaxes.

The part can hold for weeks, then drift out of tolerance, lose fastener torque, or crack at the highest stress points.

Fatigue adds another layer: vibration and repeated small loads can create micro-cracks that grow over time. The failure is often “unexpected” only because the design assumed short-term strength equals long-term reliability.

If your part must hold load for months or years, design for creep and fatigue explicitly, not as an afterthought.

Why Glass Filled Nylon Cracks Instead of Bending

When Glass Filled Nylon fails, it often cracks instead of bending because the fibers raise stiffness while reducing the material’s ability to stretch locally.

In real terms: it becomes less forgiving. A notch, thread, sharp corner, or rib root becomes a stress amplifier. Instead of yielding and redistributing load, the material concentrates stress and initiates a crack.

Once a crack starts, it can propagate fast because the part is already stiff and the fibers act like paths that guide fracture.

That is why the part may look fine right up to the moment it breaks.

If your application needs visible deformation before failure, treat high-glass grades as a reliability risk unless geometry and loading are controlled.

Glass Filled Nylon vs Unfilled Nylon vs Metal

When Glass Filled Nylon Replaces Metal Successfully

Glass Filled Nylon replaces metal when the metal’s job is stiffness, alignment, and moderate load transfer not high-impact abuse or ultra-stable tolerances across environments.

It works best when you redesign geometry (ribs, section thickness, load paths) and your failure mode is deflection, not denting or yielding.

Use it for brackets, housings, structural frames, and mounts where weight, corrosion resistance, and assembly integration matter.

It fails catastrophically when designers treat it like “plastic metal” and keep sharp corners, thin sections, and point loads. Under impact, vibration + stress concentrators, or uncontrolled fastener torque, the common mode is brittle fracture with minimal warning.

Metal typically bends first; high-glass Nylon can snap first.

Metal Swap Table:

| Metric | Glass Filled Nylon | Aluminum | Steel |

| Weight | Lowest (major mass reduction potential) | Medium | Highest |

| Corrosion resistance | High (no rust; chemical exposure still needs validation) | Medium (can pit/galvanic) | Low without coatings |

| Impact behavior | Brittle-prone (crack-driven failure) | More ductile than GF-Nylon | Most ductile / forgiving |

| Tooling cost | High upfront (mold required) | Low–medium (machining/extrusion) | Low–medium (forming/machining) |

When Metal Still Wins (And Always Will)

Metal is still the right call when you need predictable, multi-direction strength and a failure mode that is ductile instead of crack-driven.

If the part is safety-critical, sees repeated impact, or must survive uncontrolled abuse, metal is the reliability choice. Metal also wins when thin sections must carry high loads, or when stable dimensions are non-negotiable across heat and humidity.

Here’s the fatigue “gotcha” that causes late failures: metals can have a defined endurance behavior, but polymers generally do not.

Under cyclic loading, polymers accumulate damage and will eventually fail if cycled enough, even at modest stress. That makes long-life vibration parts and high-cycle mechanisms higher-risk for Glass Filled Nylon unless you validate with real duty-cycle testing and conservative stress limits.

Manufacturing & Design Constraints You Must Plan For

Injection Molding Flow Direction Risks

With Glass Filled Nylon, your gate placement is not a cosmetic choice it decides where the part is strong and where it is weak.

Flow aligns fibers, so the highest strength follows the flow path, and the weakest zones form where flow fronts meet. Those meeting points create weld lines, and weld lines behave like pre-built crack starters under load.

If your part carries stress across a weld line, expect early failure unless you redesign the flow or relocate the gate.

Treat every hole, window, and sharp transition as a flow disruptor. They create local fiber misalignment and resin-rich pockets that lose reinforcement.

If you see field cracks that “follow a line,” it is often a weld line or a flow boundary, not a random defect.

Plan for it: gate into thicker sections, keep load paths aligned with flow where possible, and avoid placing critical bosses and mounting ears in areas where two flow fronts must collide.

Glass Filled Nylon in 3D Printing (SLS & MJF) – Different Rules Apply

Glass Filled Nylon in SLS or MJF is not the same design problem as injection molding. In molding, fibers align with flow, so strength is strongest in predictable flow paths and weakest across weld lines.

In additive manufacturing, the governing factor is layer-by-layer build behavior, so the “weak direction” is tied to the build orientation and layer bonding. That means your strength and stiffness can shift significantly just by changing print orientation, even if the material name looks similar.

Treat 3D printing as different constraints: better for low-volume structural prototypes and complex geometries, but with tighter expectations on finish, tolerance, and mechanical consistency.

| Process | Fiber orientation behavior | Strength predictability | Typical use cases |

| Injection molding | Flow-driven alignment; weld lines create weak zones | High if gate + flow are controlled | High-volume structural parts, fastened housings, brackets |

| SLS / MJF | Layer-driven behavior; build direction controls weak axis | Medium; depends on orientation and process stability | Low-volume functional parts, prototypes, complex geometry components |

Expect rougher surfaces and wider tolerances than molding, and treat printed Glass Filled Nylon as “fit-validated” rather than “drop-in equivalent” unless you test actual build orientation and conditioning.

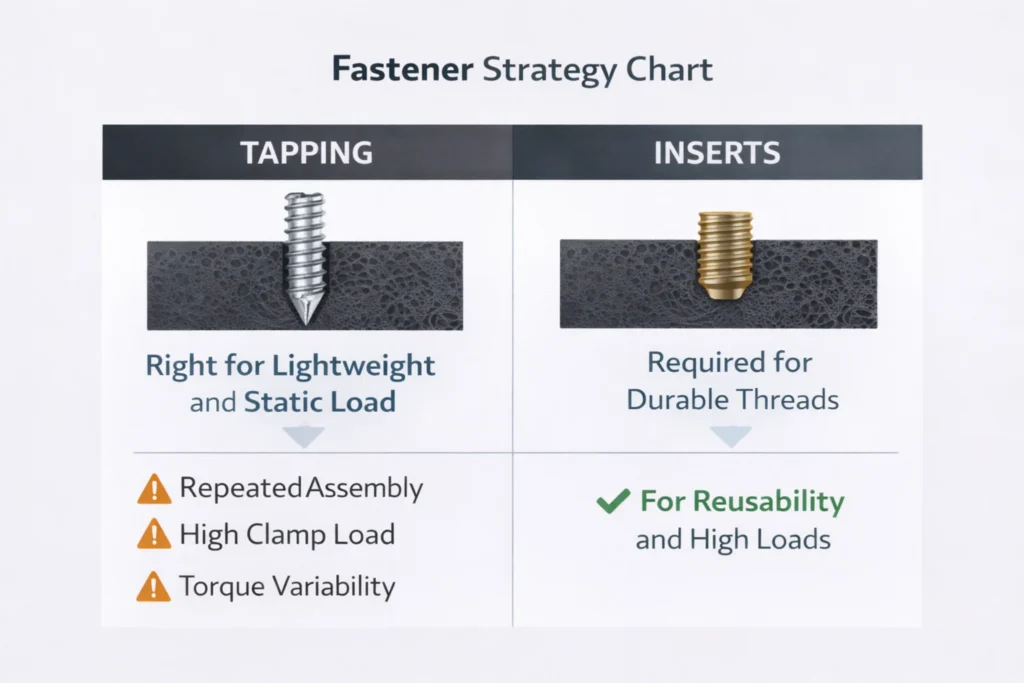

Thread Stripping, Screw Boss Failures & Inserts

Screw joints are one of the most common failure points in Glass Filled Nylon because high stiffness makes bosses less forgiving. If you overtighten, the boss does not yield smoothly it splits.

Stripping happens when the thread form is too shallow, the wall is too thin, or the screw engagement is short. The risk increases after moisture cycling and thermal aging because clamp load can relax, then reloading concentrates stress.

Use direct tapping only when loads are moderate and service access is limited. For repeated assembly, high clamp loads, or long-term retention, inserts are the safer solution.

Heat-staked or ultrasonic inserts distribute stress and reduce splitting risk, but only if boss geometry is sized correctly. If you cannot guarantee torque control, treat inserts as risk reduction not overengineering because a failed boss usually means full part replacement.

Cost vs Lifecycle Value (Is Glass Filled Nylon Worth It)?

Material Cost vs Failure Cost

Glass Filled Nylon costs more than many commodity plastics, but the real cost decision is rarely the resin price.The expensive outcome is a failure chain: cracked bosses, warped housings, loosened fasteners, field returns, and redesign time.

If a part failure triggers downtime, warranty claims, or replacement labor, the material delta becomes irrelevant. Treat this like a risk-cost calculation: pay more only when the material prevents predictable failure modes that cheaper polymers cannot reliably avoid.

If your design is stiffness-limited, creep-limited, or heat-limited, the cost premium is justified because it reduces deformation-driven defects.

If your part is impact-driven or flexibility-driven, paying for glass often buys the wrong property and increases brittle fracture risk.

Sustainability, Recycling, and ESG Considerations (2026 Reality)

Glass Filled Nylon is harder to recycle than unfilled polymers because the fiber reinforcement complicates reprocessing and limits property retention. That does not make it “non-recyclable,” but it does change what recycling means in practice.

Most real-world recycling is mechanical, and with glass-filled grades the typical outcome is downcycling into lower-demand parts, not true closed-loop reuse.

Treat sustainability here as a constraint: if your buyer has ESG gates, you justify this material by reducing failures, extending service life, and avoiding premature replacement cycles.

- Mechanical recycling is possible, but repeated processing reduces performance, so reuse is usually limited and application-specific.

- Downcycling is common: recycled material may fit non-critical components, but not tight-tolerance or high-load structural parts.

- ESG teams often accept Glass Filled Nylon when durability prevents replacements and reduced field failures offset material footprint through longer lifecycle use.

When Paying More Saves Money

Paying for Glass Filled Nylon saves money when it lets you reduce part count, eliminate metal inserts, and maintain dimensional alignment without overbuilding geometry.

It also pays off when the part must hold torque, clamp load, or positional stability over time especially near heat sources where unfilled polymers soften and creep.

Use it when you can quantify the benefit: fewer fastener issues, fewer tolerance escapes, and fewer crack-related returns.

Avoid it when the part is not performance-limited, or when your primary risk is impact abuse, operator misuse, or poor torque control.

In those cases, the premium grade does not protect you it shifts failure into sudden cracking and raises replacement cost.

Final Recommendation Who Should Use Glass Filled Nylon (And Who Should Not)

Use Glass Filled Nylon if your part must stay stiff under load, hold fastener torque, and maintain alignment at elevated temperature.

Choose it for structural housings, brackets, mounts, and frames where the primary risk is deflection, creep, or dimensional drift.

Use it when metal replacement is driven by weight, corrosion resistance, or integrated features and you can control geometry, radii, and assembly torque.

Do not use Glass Filled Nylon if your part must survive repeated impact, abuse handling, or high-flex snap behavior.

Do not use it when your design has sharp corners you cannot redesign, when weld lines will sit in high-stress zones, or when you cannot control screw torque and conditioning.

If your product needs visible bending before failure, choose a tougher polymer or metal, because Glass Filled Nylon tends to fail by brittle fracture.

Key Takeaways (Decision Summary)

- Use Glass Filled Nylon when stiffness, creep control, and heat performance drive the design—not cosmetic finish.

- Choose GF20 for moderate reinforcement and better tolerance to shock and assembly variation.

- Choose GF30 for the best balance of stiffness, creep resistance, and cost-to-performance in structural parts.

- Use GF40+ only when deformation at temperature is the failure mode and geometry is controlled.

- Plan around fiber orientation: strong in flow direction, weak across flow, and weakest at weld lines.

- Manage fastening risk: uncontrolled torque and poor boss design cause thread stripping and boss cracking.

- Treat lifecycle value as failure-cost prevention, not resin price optimization.

FAQs

Is glass filled nylon brittle?

Glass Filled Nylon can behave brittle if the design concentrates stress. High stiffness reduces the material’s ability to flex and absorb shock, so cracks start at sharp corners, ribs, threads, and weld lines. The risk increases with higher glass content and poor geometry. If the part needs impact tolerance or snap flexibility, treat Glass Filled Nylon as a brittle fracture risk unless you redesign the load path and add radii.

GF20, GF30 and GF40+ Which grade is strongest?

“Strongest” depends on how you define failure. For stiffness and load-carrying, GF40+ is typically strongest, followed by GF30, then GF20.

But higher glass content also increases notch sensitivity and crack risk. If your part sees impact, vibration, or uncontrolled torque, GF30 often delivers the best real-world strength because it balances reinforcement with better damage tolerance than GF40+.

Can it replace aluminum?

Yes, but only when aluminum’s job is stiffness, alignment, and moderate load transfer not impact absorption or ultra-stable tolerances across environments.

Glass Filled Nylon is effective in brackets, housings, and mounts when geometry is redesigned for ribs and thicker sections.

It fails when treated as a direct metal substitute with sharp corners and point loads, where brittle fracture becomes the dominant failure mode.

Does it creep over time?

Yes. Glass Filled Nylon reduces creep compared to unfilled Nylon, but it does not eliminate it. Under constant stress screw clamp load, spring force, or sustained bending the polymer matrix relaxes and dimensions drift.

Moisture and heat accelerate this behavior. If long-term load retention matters, design for creep explicitly, limit stress, and validate after conditioning, not only with short-term strength tests.