Machining ABS Plastic: Practical Guide for Precision Parts and Cost Control

Machining ABS plastic is a high reward process if you respect its thermal limits. By prioritizing sharp, single-flute tooling, maintaining a high chip load, and utilizing Machine-Grade stock, you can produce parts that rival injection-molded components in both strength and finish at a fraction of the lead time.

Is ABS Plastic a Good Choice for Machining

ABS is an excellent choice for machining when the priority is impact resistance, ease of finishing, and low material cost.

It machines cleanly, producing “curled” chips rather than fine dust, which helps maintain a clean workspace. However, success depends entirely on selecting the correct grade of raw stock before the first cut.

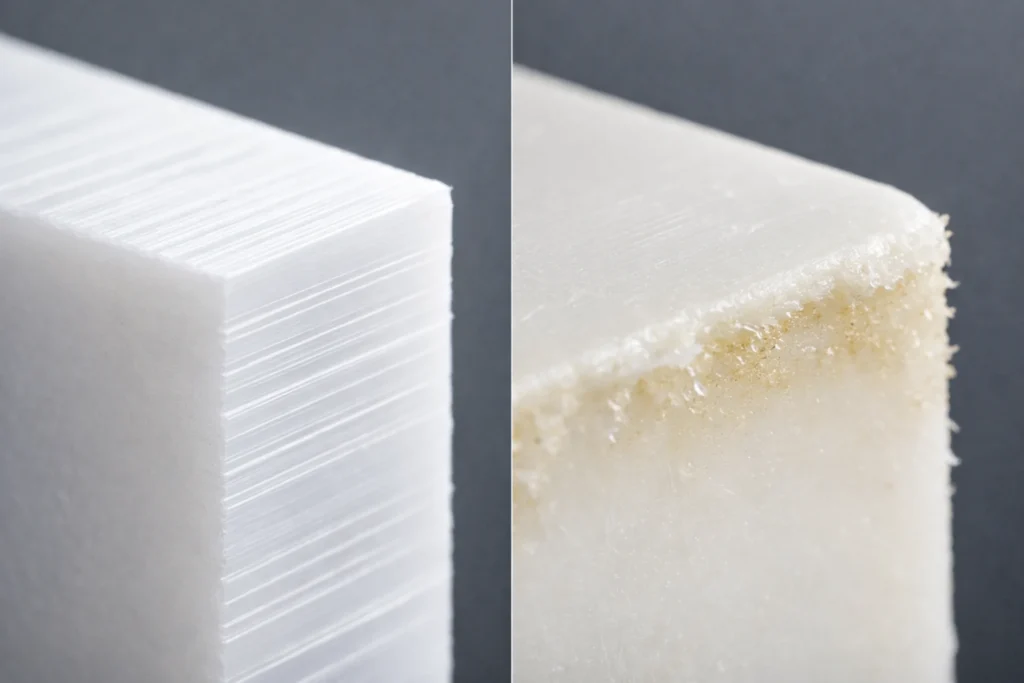

The Critical Difference: Machine-Grade vs. Injection Molding-Grade ABS

The most common cause of failure in precision ABS machining is using Molding-Grade resin blocks instead of Machine-Grade extruded plates or rods. While chemically similar, their physical behavior under a cutting tool is vastly different.

| Feature | Machine-Grade (Extruded/Compression) | Injection Molding-Grade (Resin/Cast) |

| Internal Stress | Low (Relieved during extrusion) | High (Residual stress from cooling) |

| Thermal Stability | High (Maintains shape during cutting) | Poor (Prone to localized melting) |

| Dimensional Goal | Precision Tolerances | General Prototyping |

| Machinability | Excellent; crisp edges. | Poor; “gums” up the tool flutes. |

Machinability Characteristics of ABS Compared to Other Plastics

To understand how ABS performs in the shop, use this 1–5 scale (5 being best) relative to other common engineering plastics like Delrin (POM), PEEK, and Acrylic.

- Surface Finish: 5/5 – Exceptional. Capable of achieving high-gloss finishes with minimal post-processing.

- Tool Wear: 5/5 – Non-abrasive. A single carbide end mill can last for hundreds of parts without losing its edge.

- Structural Rigidity: 3/5 – Good, but will flex under heavy clamping or aggressive feed rates.

- Heat Resistance: 2/5 – Weak Point. ABS has a low glass transition temperature; it will melt if the chip load is too low or the RPM is too high.

When ABS Machining Makes Sense and When It Doesn’t

Use the following criteria to validate your material selection. ABS is a specialized tool, not a “one-size-fits-all” solution.

Choose ABS for:

- High-Impact Applications: Protective housings, handheld device enclosures, and rugged industrial bezels.

- Complex Assemblies: Parts that require solvent bonding or chemical welding to create airtight seals.

- Secondary Aesthetics: Components that need to be painted, chrome-plated, or vapor-polished.

- Budget-Sensitive Projects: When you need a “real” plastic feel at roughly 30-40% the cost of Delrin.

Avoid ABS for:

- High-Temperature Environments: Do not use if the operating environment exceeds 70°C (158°F); the part will lose structural integrity.

- High-Friction Wear Parts: Avoid for gears, bushings, or sliding surfaces. Use Delrin (POM) or Nylon instead.

- Outdoor UV Exposure: Standard ABS yellows and becomes brittle in sunlight. Use ASA for UV-stable applications.

- Extreme Chemical Exposure: ABS dissolves in acetone and is weakened by many petroleum-based lubricants.

Key Challenges When Machining ABS Plastic

Heat Buildup, Melting, and Edge Deformation

The absolute thermal threshold for ABS is its glass transition temperature: 105°C (221°F). Once the tool interface hits this temperature, the material stops “chipping” and starts “smearing.”

- The “Rubbing” Trap: Melting is rarely caused by high speeds alone; it is caused by rubbing. If your feed rate is too slow or your tool is dull, the cutter rubs against the plastic, generating friction heat that cannot escape.

- Edge Deformation: Excessive heat causes the edges of your cuts to “roll over” or develop a burr that is difficult to remove without scarring the surface.

- The Solution: Use high-feed rates to ensure the heat is carried away in the chip itself, not left behind in the workpiece.

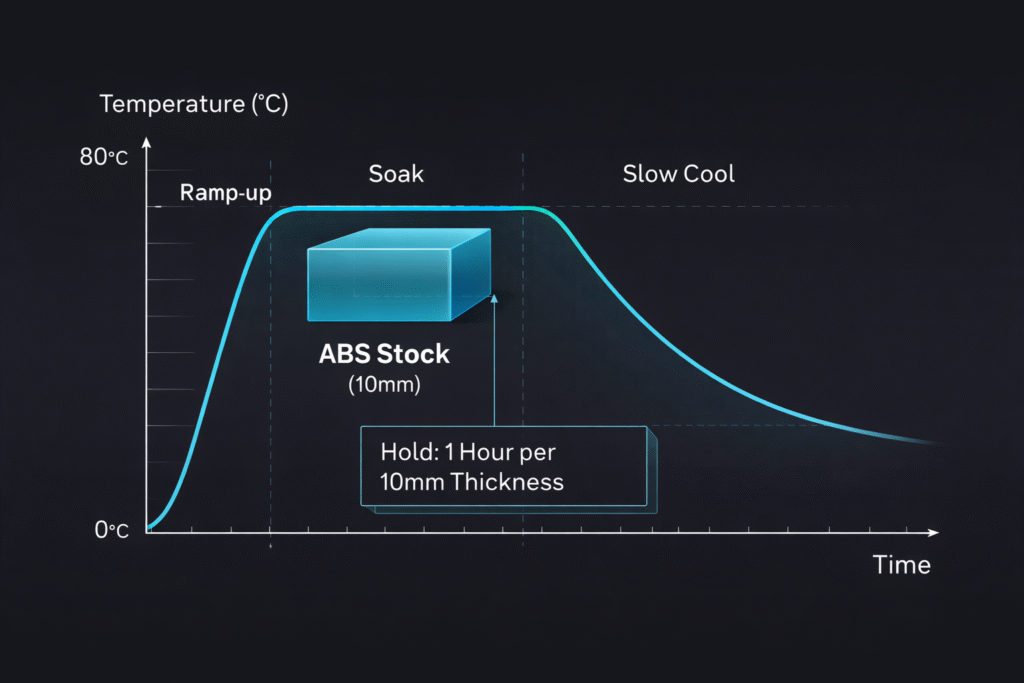

Dimensional Stability and the Role of Annealing

ABS is prone to “stress-walking” where a part dimensions change hours or days after machining because internal stresses were “unlocked” during material removal. For high-precision components, an annealing cycle is mandatory to stabilize the molecular structure.

The Professional ABS Annealing Cycle:

- Heating: Place the ABS stock in a circulating air oven and increase the temperature to 80°C (175°F).

- Soaking: Hold this temperature for 1 hour for every 10mm of thickness.

- Cooling: Decrease the temperature gradually (no more than 10°C per hour) until it reaches room temperature.

Pro Tip: Never “quench” ABS or remove it from the oven while hot. Rapid cooling re-introduces the very stress you are trying to eliminate.

Tolerance Limitations and “Machined-In” Stress

While CNC machines are capable of micron-level precision, ABS is a flexible polymer that “breathes” with temperature and humidity. You must set realistic engineering expectations.

- Standard Tolerance: ±0.1mm (0.004”) is easily achievable for most ABS parts.

- Precision Tolerance: ±0.05mm (0.002”) is possible but requires stabilized (annealed) stock and a climate-controlled machining environment.

- The “Spring-Back” Effect: Because ABS is elastic, it may compress slightly under tool pressure and “spring back” once the tool passes. Always use razor-sharp, up-cut geometry to minimize downward pressure on the part.

Recommended Tools and Cutting Parameters for ABS

Tool Geometry, Sharpness, and Material Selection

Tool selection is the single most important factor in preventing ABS from melting. You must prioritize sharpness and chip clearance over tool longevity or coating technology.

- Material Choice: Use Uncoated Carbide or High-Speed Steel (HSS). Avoid TiAlN or other dark coatings designed for heat resistance in metals; these coatings actually round the cutting edge at a microscopic level, increasing friction in plastics.

- Flute Count: Strictly use 1-flute or 2-flute end mills. 3 or 4-flute tools do not have enough “gullet” space to eject the large, curled chips that ABS produces.

- Geometry: Demand High Rake Angles and Polished Flutes. A polished flute reduces the coefficient of friction, allowing the plastic chip to slide up and out before it has a chance to heat up and stick to the tool.

- The “O-Flute” Advantage: For high-speed routing of ABS sheet, an Up-cut O-Flute is the industry standard for achieving a burr-free finish.

Feeds, Speeds, and Chip Control for Clean Cuts

The following parameters are engineered to ensure the heat stays in the chip, not the part. Use these as your baseline starting points:

Master Parameter Table: CNC Machining ABS

| Operation | Spindle Speed (RPM) | Feed Rate (per tooth) | Cutting Depth (DOC) | Cooling Requirement |

| Roughing | 1,500 – 2,500 | 0.20 – 0.30 mm | Up to 1x Tool Dia | High-Pressure Air |

| Finishing | 3,000 – 4,500 | 0.05 – 0.08 mm | 0.25 mm | Water-Soluble Mist |

| Drilling | 500 – 1,000 | 0.10 – 0.15 mm | Peck every 3mm | Mist or Flood |

Critical Chip Control Rules:

- Avoid Dry Machining: While ABS can be cut dry, a constant Air Blast is mandatory to clear chips. If the tool recuts a chip, it will melt.

- Direction: Always use Climb Milling. This produces a chip that starts thick and thins out, which helps pull heat away from the tool’s point of entry.

- The “Crust” Effect: If you see “strings” or “hair” on the part after a cut, your feed rate is too slow. Increase your feed to take a larger bite and move the heat out faster.

Surface Finish and Post-Machining Quality Control

Achieving Acceptable Surface Finish on ABS

The quality of your “as-machined” surface depends on your final tool path strategy. Because ABS is relatively soft, it is susceptible to “tool marks” if the setup is not rigid.

- The Final “Clean-up” Pass: Never attempt to achieve a final finish during a heavy stock-removal cut. Leave 0.20mm to 0.30mm of material for a final finishing pass at a higher RPM.

- Climb Milling vs. Conventional: Always utilize Climb Milling for finishing. In ABS, conventional milling tends to “lift” the material fibers, resulting in a fuzzy or “hairy” surface. Climb milling pushes the material down, creating a crisp, sheared edge.

- Tool Engagement: Ensure the tool is constantly moving. If the spindle dwells in one spot for even a second, the friction will create a visible “melt mark” or “divot” on the surface.

Secondary Operations: Deburring, Polishing, and Bonding

One of the greatest advantages of ABS is how easily it can be modified after it leaves the CNC bed.

- Vapor Smoothing (The Pro Secret): To achieve a “molded” high-gloss look, use Acetone Vapor Smoothing. Briefly exposing the part to acetone vapor (typically 30–60 seconds in a controlled chamber) melts the outermost microscopic layer, instantly erasing tool marks and sealing the surface.

- Deburring: Avoid using high-speed rotary deburring tools, which can melt the edges. Use fixed-blade ceramic scrapers or specialized plastic deburring swivel blades for the cleanest results.

- Solvent Welding: You can bond ABS parts to create complex geometries that are impossible to machine in one piece. Use MEK (Methyl Ethyl Ketone) or specialized ABS solvent cements. These don’t just “glue” the parts; they chemically melt the interface to create a monolithic bond that is as strong as the base material.

- Mechanical Polishing: For optical clarity or high shine, ABS responds well to standard buffing wheels using fine-grit compounds. Always keep the wheel moving to prevent localized heat deformation.

ABS Machining vs Injection Molding

Cost, Lead Time, and Volume Break-Even Points

The “Best” method is determined almost entirely by your production volume. Injection molding requires expensive steel or aluminum tooling (Capex), whereas CNC machining incurs higher per-part costs (Opex).

- The 200-Unit Rule: As a standard industry rule of thumb, CNC machining is the more cost-effective choice for 1 to 200 units.

- The Transition Zone: Between 200 and 1,000 units, you enter a “grey area” where Bridge Tooling (Rapid Molding) becomes competitive.

- Molding Dominance: Once you exceed 1,000 units, the high initial cost of the mold is amortized, and injection molding becomes significantly cheaper per part.

- Lead Time Comparison:

- CNC Machining: 3–5 days (From CAD to part).

- Injection Molding: 4–8 weeks (Due to tool design, fabrication, and T1 samples).

Prototype vs Production Decision Framework

Before committing to a manufacturing method, run your design through this engineering checklist. If you answer “No” to more than two of these, CNC Machining is your required path.

| Decision Criteria | Requirement for Injection Molding | CNC Machining Advantage |

| Wall Thickness | Must be Uniform (approx. 2mm-3mm). | Can handle thick/variable sections. |

| Draft Angles | Requires 1.5° to 3° for part ejection. | Can machine 90° vertical walls. |

| Internal Ribs | Necessary to prevent “sink marks.” | Not required; can machine solid blocks. |

| Undericuts | Require expensive “sliders” or “lifts.” | Easily handled by multi-axis setups. |

| Design Maturity | Must be final. Changes cost $1,000s. | Changes are instant via CAD update. |

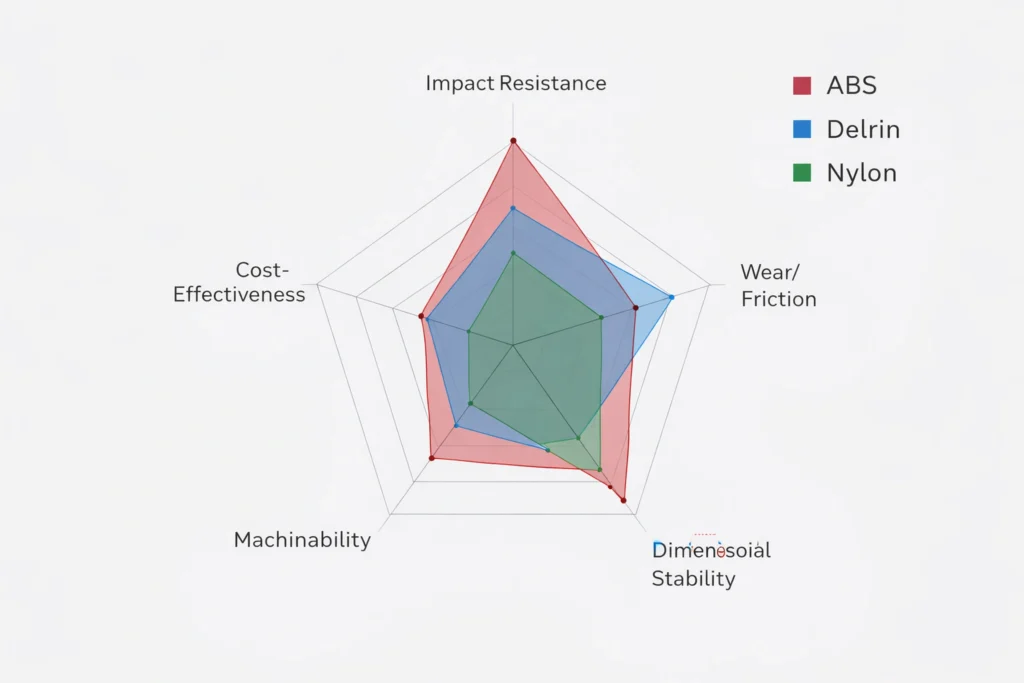

ABS vs Delrin and Nylon for Machined Parts

Choosing the wrong plastic can lead to premature part failure or unnecessary cost overruns. While ABS is a versatile workhorse, it competes directly with Delrin (Acetal) and Nylon (PA6). The following comparison identifies exactly where ABS wins and where it falls short.

Strength, Wear, and Friction Comparison

Use this technical table to match your part’s functional requirements with the correct material properties.

| Feature | ABS (Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene) | Delrin (Acetal/POM) | Nylon (Polyamide/PA6) |

| Primary Strength | Impact Resistance | Dimensional Stability | Toughness & Wear |

| Machinability | Excellent (Easy to finish) | Superior (Cuts like brass) | Good (Prone to burring) |

| Coefficient of Friction | High (Sticky) | Very Low (Slippery) | Low (Self-lubricating) |

| Moisture Absorption | Low (<0.3%) | Very Low (<0.2%) | High (Up to 8% – swells) |

| Best Application | Housings & Enclosures | Gears & Bearings | Bushings & Rollers |

| Cost Profile | Most Budget-Friendly | Premium ($$$) | Moderate ($$) |

Selecting the Right Plastic Based on Application Load

To ensure your part survives its lifecycle, follow these application-specific selection rules:

- Choose ABS if: Your part will be subjected to sudden impacts or “drops” (e.g., a handheld remote). It absorbs energy better than Delrin, which can be brittle under high-velocity impact. ABS is also the only choice in this group that allows for easy painting and solvent welding.

- Choose Delrin (POM) if: You need tight tolerances (±0.02mm). Delrin is stiffer and does not “creep” or deform under constant load. It is the gold standard for mechanical components like gears, cams, and precision spacers.

- Choose Nylon if: The part faces continuous abrasion. Nylon (PA 6/6) has incredible wear resistance, but beware of its “hygroscopic” nature, it absorbs water from the air, which causes the part to grow in size. Never use Nylon for high-precision parts in humid environments.

Typical Applications of Machined ABS Parts

Industries and Specific Use Cases

Below are six specific applications where machined ABS is the industry standard. These examples highlight the material’s balance of impact strength and surface versatility.

| Application | Why ABS is Specified | Key Requirement |

| Electronic Enclosures | Excellent dielectric properties and impact resistance for handheld devices. | RF Transparency |

| Automotive Prototypes | Used for interior trim, dashboard bezels, and console prototypes before molding. | Paintability |

| Fluid Manifolds | Easy to machine deep internal channels; can be solvent-welded for complex paths. | Airtight Seals |

| Industrial Fixtures | Low-cost material for non-marring assembly jigs and alignment tools. | Rigidity/Cost |

| Medical Housings | Used for non-invasive device covers and diagnostic equipment shells. | Chemical Bonding |

| Architectural Models | High level of detail and ability to achieve a “Class-A” polished finish. | Aesthetics |

Safety and Environmental Considerations for ABS Machining

Fume Management: Handling VOC Emissions During Overheating

While you are not “burning” the plastic, the heat generated at the tool tip during CNC operations is often high enough to reach the point of thermal degradation.

- The Hazard: Overheated ABS releases Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs), most notably Styrene gas. Styrene is a respiratory irritant and a suspected carcinogen; prolonged exposure can cause headaches, dizziness, and fatigue.

- The Warning Sign: If you smell a distinct “burnt plastic” or acrid odor, the material is already off-gassing toxic fumes.

- Mandatory Controls:

- Local Exhaust Ventilation (LEV): Always use a vacuum or fume extraction system positioned directly at the spindle.

- Air Exchange: Ensure the machine shop has a minimum of 6–10 air changes per hour.

- Coolant Usage: Using a water-soluble mist or air blast doesn’t just protect the tool it keeps the material below the smoke point, preventing fumes from forming.

UV Sensitivity and Outdoor Application Risks

A common engineering mistake is specifying machined ABS for outdoor equipment without understanding its photochemistry.

- The Degradation Timeline: Standard ABS is not UV-stable. When exposed to direct sunlight, the Butadiene component breaks down. You will see visible yellowing and chalking within 3–6 months, followed by a 50% loss in impact strength within 12 months.

- Environmental Stress Cracking: ABS is sensitive to “stress cracking” when exposed to certain outdoor pollutants and cleaning agents while under mechanical load.

- The Professional Alternative: If your machined part must survive outdoors, switch to ASA (Acrylonitrile Styrene Acrylate).

- Why ASA? It machines identically to ABS and has nearly the same cost, but it uses an acrylic elastomer that is inherently resistant to UV radiation and weather-induced brittleness.

Final Decision Checklist for Machining ABS Plastic

Engineering Criteria Before Material Approval

If you can answer “YES” to all five of the following points, ABS is the optimal material for your machined part.

- Impact vs. Rigidity: Does the application require the part to survive a drop or sudden impact without shattering (unlike Acrylic or some Acetal grades)? [ ] Yes

- Thermal Operating Range: Will the part operate exclusively in environments below 70°C (158°F)? [ ] Yes

- Chemical Environment: Is the part free from contact with Acetone, Esters, or Ketones that would cause immediate material dissolution? [ ] Yes

- Aesthetic Requirements: Does the project require secondary finishing like painting, solvent bonding, or high-gloss polishing? [ ] Yes

- UV Exposure: Is the part intended for indoor use, or will it be protected by a UV-resistant coating if used outdoors? [ ] Yes

Cost and Performance Trade-Off Summary

To finalize your decision, compare the “Value vs. Risk” profile of ABS:

- The “Win”: You are choosing a material that is easy to machine, has zero moisture absorption issues, and offers the lowest price-per-cubic-inch of any engineering-grade thermoplastic (Glass filled nylon, or PA 11)

- The “Risk”: You must account for thermal expansion and the necessity of Annealing if your tolerances are tighter than ±0.05mm.

Final Verdict: ABS is the superior choice for functional enclosures, impact-resistant brackets, and visual prototypes. If your part requires precision gear-teeth or 24/7 outdoor exposure, revisit the Delrin or ASA sections of this guide.

FAQs

Is ABS plastic easy to machine?

Yes, ABS is widely considered one of the easiest engineering plastics to machine. It is non-abrasive, chips cleanly without excessive dust, and allows for excellent surface finishes. However, its low melting point requires careful management of cutting speeds and feed rates to prevent thermal deformation.

How do you prevent ABS plastic from melting during CNC machining?

To prevent melting, use sharp, single or two-flute carbide tools to ensure efficient chip evacuation. Maintain a high feed rate and lower spindle speeds (1,000–3,000 RPM) to ensure the tool shears the plastic rather than rubbing it. Constant air blast or water-soluble coolant is also mandatory.

What is the difference between ABS and Delrin for machined parts?

While both machine well, Delrin (POM) offers superior dimensional stability, lower friction, and better wear resistance for mechanical parts like gears. ABS is more cost-effective, has higher impact resistance, and is much easier to paint or solvent-bond.

Why should you anneal ABS plastic before machining?

Annealing relieves the internal stresses trapped in ABS during the extrusion process. Without annealing, the material may warp or “walk” out of tolerance hours after machining as the removed material “unlocks” these stresses. Standard cycles involve heating to 80°C (175°F) and slow-cooling.

Can you achieve a high-gloss finish on machined ABS?

Yes. Beyond standard mechanical polishing, ABS can achieve a “molded” high-gloss finish through acetone vapor smoothing. Because ABS dissolves in acetone, a short exposure to the vapor melts the outermost microscopic layer, instantly erasing tool marks and sealing the surface.

Is machined ABS plastic UV stable for outdoor use?

Standard ABS is not UV stable and will yellow, chalk, and become brittle within 6–12 months of direct sunlight exposure. For outdoor applications, engineers should specify ASA (Acrylonitrile Styrene Acrylate), which machines identically to ABS but contains an acrylic elastomer that resists UV degradation.