Nylon for Machining: Grades, Machinability, Tolerances, and When to Use It

Is Nylon a Good Material for Machining?

Yes, nylon is an excellent choice for CNC machining but it is a “paradox” material. While it is easy to cut and produces functional parts rapidly due to its toughness and lightweight nature, it is famously difficult to hold to tight tolerances.

Because nylon is hygroscopic (moisture-absorbing) and has a high thermal expansion coefficient, it “moves” both during and after the machining process.

To succeed with nylon, you must balance its high-performance properties against its tendency to gum or smear when heat builds up.

| Property | Value | Benefit |

| Density (Nylon 6) | ~1.14 g/cm³ | Major weight savings vs metals |

| Tensile strength @ break (Nylon 6) | ~82.7 MPa | strong enough for many load bearing plastic parts |

| Water absorption @ 24 h (ASTM D570) | ~1.8% | Predict / Plan for tolerance shift in humid service |

| Low-friction options (oil-filled nylon) | ~25% lower COF vs standard nylon | Reduce wear, less squeal, less lube dependency |

| Mechanical damping (engineered nylons) | “High” damping capacity | Quieter running parts (gears, guides, wear strips) |

When Nylon Performs Well in Machined Parts

- Wear parts: gears, bearings, bushings, guides, wear pads

- Low-noise mechanisms: damping helps reduce rattle and chatter

- Medical/automation components where lightweight + toughness matter

- Lightweight EV components (e.g., gears and electrical/connector systems) where polymers help reduce mass and simplify assemblies

Where Machining Nylon Causes Problems

Nylon’s biggest machining failures come from heat + moisture. It doesn’t conduct heat well, so friction concentrates at the cutting edge especially in drilling leading to gumming, melted/smeared surfaces, and distorted holes when chips aren’t cleared or tools are dull.

Add moisture absorption on top, and a “perfect” dimension on the machine can drift later as the part equilibrates with its environment, which is why tolerance planning matters more with nylon than with inherently stable plastics like acetal.

Which Nylon Grades Are Best for Machining?

“Best” depends on what you’re optimizing: chip formation, dimensional stability, heat performance, or regulatory needs.

Nylons differ in crystallinity and in how strongly they attract water (more amide groups per chain generally means more moisture uptake).

In machining terms, that shows up as: how gummy the cut feels, how much the part moves with shop humidity, and how close you can hold tolerance without post-conditioning.

| Grade | Moisture absorption % (24 h) | Heat deflection temp (1.8 MPa) | Best use case |

| PA6 (Nylon 6) | 1.28% | 70 °C | Tough general-purpose parts, wear pads, prototypes |

| PA66 (Nylon 6/6) | 0.70% | 85 °C | Stiffer parts with better heat resistance; tighter fits at elevated temp |

| PA12 (Nylon 12) | 0.20% | 45 °C | chosen for medical/lab components |

| PA66-GF30 (30% glass-filled) | 0.30% | 150 °C | High-stiffness, high-temp housings/brackets where wear against mating parts is acceptable |

A practical selection rule: if the part is a wear component and you can allow “plastic tolerances” (or you’ll machine after conditioning), PA6 is usually the easiest win.

If you need more stiffness and temperature margin, PA66 is the step up.

If your biggest enemy is dimensional drift from humidity, common in tight-fit medical fixtures, pneumatic manifolds, or precision components, PA12 is a favorite because PA12 absorbs little water and shows minimal dimensional change as humidity varies.

Nylon 6 vs Nylon 6/6 in CNC Machining

Nylon 6 (PA6) is typically the “tough, forgiving” choice. It machines with less brittle chipping and absorbs vibration well, which helps in parts like gears and wear pads.

Nylon 6/6 (PA66) runs stiffer and hotter. Its higher melting point is a good clue (about 260 °C vs. ~220 °C for PA6), and that usually translates to better heat resistance and less creep under load useful near motors, pumps, or warm fluids.

Cast Nylon vs Extruded Nylon

Cast (monomer-cast) nylon

- Pros: lower internal stress → less warping after heavy stock removal; ideal for large parts

- Cons: broader property variation through thick sections; sometimes longer lead times

Extruded nylon

- Pros: economical and widely stocked; great for small/simple parts and prototypes

- Cons: higher residual stress; for tight tolerances, pre-annealing and balanced stock removal can prevent “potato-chipping”

Glass-Filled Nylon (Machinability Trade-offs)

- Stiffness jump: GF30 compounds often move from ~3–3.5 GPa tensile modulus (unfilled PA66) to ~7–10 GPa, which is why designers describe “about triple” stiffness in the dry condition.

- Tooling reality: glass fibers are abrasive; standard HSS tools dull quickly use sharp carbide, and consider diamond/DLC/PCD tooling for long runs.

- Process tweaks: reduce surface speed, keep chip load high enough to cut (not rub), and use air blast/mist for chip evacuation and temperature control.

- Tribology warning: GF30 gains rigidity but can be rough on mating surfaces; avoid it for sliding bearings unless the counterpart is selected for it (or switch to an internally lubricated nylon grade).

Machining Properties That Matter (Real-World Behavior)

Nylon feels “easy” to machine because cutting forces are low but it’s harder to hold size because it’s viscoelastic. It deflects under tool pressure, warms up locally, and then springs back after unclamping or cooling.

The physics shows up in two numbers: PA6’s linear thermal expansion is about 80–90 ×10⁻⁶/K—compare this to Aluminum at ~23 or Carbon Steel at ~12.

This massive difference illustrates why nylon ‘moves’ several times more than metals during a temperature swing, making it a challenge for precision assemblies.

Moisture Absorption and Dimensional Stability

Nylon is also moisture-sensitive; “dry today vs. humid tomorrow” is a real tolerance stack-up driver.

Annealing and conditioning to prevent spring back

- Pre-dry (tight-tolerance workflow): For critical features (<±0.05 mm), dry the blank in a circulating oven at 80°C for ~8 hours, then cool and keep sealed until machining. Many nylon processing guides target <0.2% moisture; if moisture is elevated, published drying tables show that 80°C cycles can extend into the 8–24 hour range.

- Rough in a balanced way: Remove stock symmetrically (both sides of the centerline) to minimize warp from stress release.

- Rest before finish: After roughing, let parts sit for hours (or overnight) so recovery/stress relaxation happens before you “dial in” final size.

- Use stress-relief annealing only when needed: If you’re hogging material or chasing flatness, intermediate annealing can help; one common stock-shape guideline for Cast Nylon uses a slow heat-up to ~300°F (149°C) with hold/cool steps tied to thickness.

Note: For Extruded Nylon 6/6, keep temperatures lower or use an inert environment, as the material can begin to oxidize and yellow at these levels

- Inspect at equilibrium: Measure at stable shop temperature/humidity and document the conditioning state (dry-as-machined vs. conditioned-in-service).

Thermal Softening and Heat Buildup

Nylon’s low heat conduction concentrates temperature at the edge; drilling is especially prone to gumming because chips are trapped in a confined space.

- Air blast / mist (preferred): clears chips and cools gently without soaking a hygroscopic polymer.

- Flood coolant (cautious): can promote chip recutting and (if water-based) adds a moisture pathway that can nudge dimensions on precision parts.

Chip Formation, Stringing, and Surface Finish

Troubleshooting: “birds’ nests” and smeared surfaces

- Symptom: long stringy chips wrap the tool; finish looks glossy/smeared.

- Why: feed too low (rubbing), dull edge, or chips being re-cut each raises interface heat.

- Fix: raise feed into a true-cutting regime (turning rough often behaves best around 0.2–0.3 mm/rev), keep a sharp positive-rake edge, and evacuate chips aggressively with air/vacuum.

CNC Machining Guidelines for Nylon (Practical Rules)

If you want nylon parts that measure right and stay right, your job is simple: keep it cutting (not rubbing), keep it cool, and keep it supported.

The NYCAST cast-nylon guidelines are blunt about the fundamentals: high speeds, heavy-enough feeds, sharp/high-rake tools, and full support.

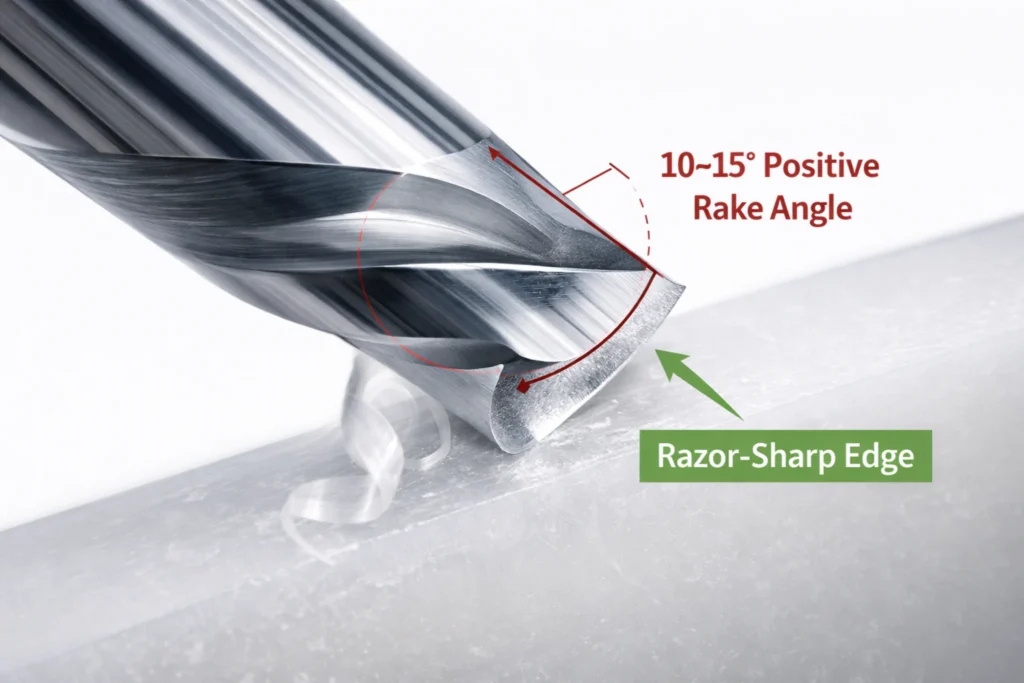

Tooling Selection (Cutters, Geometry, Coatings)

Use this as your “buy once, cry once” nylon tool spec:

- Tool material: sharp polished carbide for best life + finish (especially for production).

- Geometry: positive rake 10–15° (in the plastics sweet spot of ~5–15°) with generous clearance to reduce heat and cutting forces.

- Flutes: 1–2 flute / O-flute style cutters for aggressive chip evacuation in softer plastics.

- Edge condition: razor-sharp / lightly honed (avoid edge chipping, but don’t “round” the edge into a rubbing tool).

- Coatings:

- DLC-coated carbide when you fight built-up edge, heat, or adhesion in engineering plastics.

- Diamond/PCD when machining abrasive filled grades (glass/carbon reinforced) for tool life.

- Do not use “old metal” tools: NYCAST explicitly warns drills previously used on metal should never be used for nylons (dull edges = grabbing, heat, cracking). Apply that logic to end mills and taps too.

Feeds, Speeds, and Depth of Cut

Copy-paste starting parameters (PA6 / cast nylon, sharp carbide, good chip evacuation):

(Adjust down for thin walls, long stick-out, or gummy/oil-filled grades; adjust up if you’re rubbing and stringing.)

| Operation | Speed (m/min) | Feed (mm/rev) |

| Turning — Rough | 180–305 (600–1000 SFM) | 0.25–0.50 |

| Turning — Finish | 180–305 | 0.08–0.18 (lighter, for size) |

| Milling — Rough (2-flute) | 305–1200 (1000–4000 SFM) | 0.50–1.02 (from 0.25–0.51 mm/tooth ×2) |

| Milling — Finish (2-flute) | 305–1200 | 0.20–0.60 (lighter to control deflection) |

| Drilling — General | ≤107 (≤350 fpm) | 0.10–0.38 |

Depth-of-cut reality check: NYCAST notes roughing cuts can be quite heavy on rigid setups, but finishing should be lighter and it even recommends a 24-hour relax period before the final pass when possible.

Checklist before you hit Cycle Start

- Aim for chips, not dust: increase chip load until you’re shearing cleanly (dust = rubbing = heat).

- Air blast first: spray air/mist is highly effective at cooling the cutting interface for plastics.

- Drilling rule: peck often (NYCAST suggests pull-out every ≤0.5×D) to evacuate chips and prevent gumming/melted walls.

Note: Nylon tends to ‘close in’ after drilling; always use a slightly oversized drill or a reamer if the final bore diameter is critical.

- Support everything: fully support the work piece in milling; nylon will deform under clamp and cutter load.

Post-Processing Nylon Parts (Polishing, Dyeing, Vapor Honing)

Polishing: For cosmetic parts, hand sanding then plastic polish works but keep heat low (friction can smear). For functional parts, a light deburr plus controlled abrasion is usually better than chasing a “mirror” that changes dimensions.

Dyeing (color-coded industrial parts): Nylon takes dye well when heated; common shop methods keep the bath around ~82°C (180°F) to maintain uptake and uniformity.

Vapor honing (“frosted medical” look): Wet blasting/vapor honing uses a water + media slurry to create a clean, uniform satin texture, popular where you want a consistent matte finish without the harshness of dry blasting.

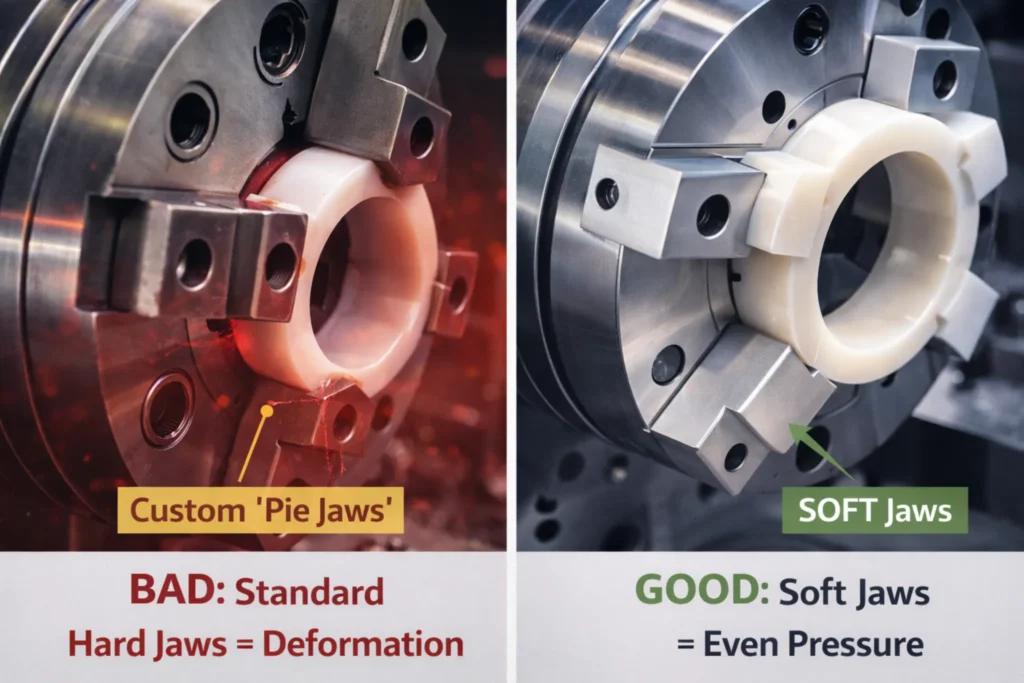

Workholding, Clamping, and Stress Relief

Pro-Tip (saves more parts than fancy tooling): Clamp gently.

Use soft jaws, wide contact pads, and full support so the part can’t “dish” under clamping.

NYCAST specifically warns that clamping/holding must avoid deformation and recommends support during all milling operations.

For tight-tolerance work: rough → rest (or relax) → finish, because nylon will spring back after unclamping and after heat dissipates.

Tolerances, Warping, and Post-Machining Issues

With nylon, the machine can hit a number that the material won’t keep. The difference between theoretical tolerance (what your CNC and probes can measure right now) and achievable tolerance (what still fits after temperature changes, unclamping, and humidity exposure) is the whole game.

Nylatech specifically notes that frictional heat expands nylon and recommends leaving a final pass, letting the part sit overnight, then taking the last cut for tight fits.

Warping and “mystery” size drift usually comes from two sources: residual stress (especially if you remove a lot of stock from one side) and moisture uptake (nylon is hygroscopic and changes dimension as it absorbs water).

If you’re chasing flatness or special tolerances, cast-nylon machining guidance even calls out intermediate/post machining annealing as a way to improve dimensional stability.

Achievable Tolerances in Nylon Parts

A realistic “shop-standard” target for most machined nylon features is about ±0.08 mm (±0.003″) and tighter usually requires tighter controls (material conditioning + stable inspection conditions).

- Typical practical target: ±0.08 mm on most critical dimensions when temperature/humidity are stable (think: one side machined, rested, then finished).

- ISO-style guidance (plastics, fine): ±0.05 mm (0.5–6 mm), ±0.10 mm (6–30 mm), ±0.15 mm (30–120 mm).

- What many general suppliers default to for plastics: ±0.25 mm (±0.010″) unless you call out tighter.

- Holes are special: reamed/boring features can be held tighter than general stock removal, but nylon still needs controlled heat + moisture to stay there.

Dry-As-Machined vs Conditioned Nylon

Before (Dry-as-machined in a dry shop):

- Parts measure “perfect” right after cutting because the polymer is warm and relatively dry.

After (Conditioned in a humid factory / normal atmosphere):

- Nylon absorbs moisture toward an equilibrium level (e.g., nylon 6 is often cited around 3.5% at 23°C/60% RH), and water absorption results in dimensional change so parts can grow and clearances can disappear.

If your assembly lives in changing humidity, specify tolerances around the conditioned state (or control moisture during storage/inspection), otherwise you’re only proving the part fits on the day it left the machine.

When Secondary Machining Fails

Secondary ops (reaming, tapping, boring-to-size, spotfacing) are where nylon most often “looks perfect” on the machine and then fails in assembly.

The root cause is usually a mix of heat + spring-back + moisture shift: nylon expands from frictional heat, then relaxes after cooling/unclamping, and later changes size again as it equilibrates with ambient humidity.

The most common failure patterns:

- Reaming that “polishes” instead of cuts: If you try to remove too little stock, the reamer rubs, heats the bore, and the hole rebounds undersize after cooling.

A cast-nylon machining guide notes it’s difficult to remove less than 0.002 in when reaming and recommends leaving ~0.005 in for the final ream so the tool has a real bite.

- Threads that feel tight… then loosen or strip: Nylon’s resiliency plus tool wear is brutal on thread quality. Use sharp taps only and never taps previously used on metal. For cast nylons, oversize taps (e.g., H-3 for smaller, H-5 for larger) and an oversize of about 0.002–0.005 in (0.05–0.13 mm) are specifically recommended to account for elastic recovery.

- Bores that go oval / crack after drilling: Drilling can generate extreme frictional heat and trapped chips, leading to gumming, melted hole walls, and even stress cracking.

Peck drilling (withdraw frequently) and coolant as mist/flood are called out as essential; one guide suggests pecking no deeper than ½×D per peck to clear chips.

Practical rule: do secondary machining only after the part is thermally stable, machine to within one pass, let it sit, then take the last sizing cut for interference or precision fits.

Nylon vs Other Machining Plastics (Decision Comparison)

If you’re choosing between “machine-friendly” plastics, the real decision is usually wear vs. dimensional stability.

Nylon is a strong metal-replacement when parts slide, impact, or need damping but it can move with humidity.

Acetal (POM/Delrin) is the go-to when you need parts to stay on-size across environmental changes because its moisture absorption is far lower.

| Material | Dimensional stability | Wear / impact | Moisture sensitivity | Machining feel | Best-fit use case |

| Nylon (PA6/PA66) | Medium (can drift) | High toughness/abrasion | High | Can get “gummy” if rubbed | Wear pads, gears, bushings, quiet mechanisms |

| Acetal (POM/Delrin) | High (holds tolerance) | Medium–high | Low | Crisp, clean cutting | Precision gears, valve parts, tight-fit components |

| UHMW-PE | Low (creeps/deflects) | Very high abrasion/impact | Low | very stringy chip wrap risk | Liners, guides, conveyor wear strips |

| PETG | Medium–high | Low–medium | Low–medium | Easy, cosmetic-friendly | Guards, covers, low-load fixtures |

| PEEK | Very high (thermal stability) | High | Low | Demands sharp tools/heat control | High- temp,chemical,sterilizable parts |

Nylon vs Acetal (POM)

This is the classic “Nylon vs Delrin” call. If your #1 requirement is holding tight tolerances, acetal usually wins because its moisture absorption is roughly an order of magnitude lower (Delrin ~0.20–0.25% at 24h vs. nylon examples around ~1.3%).

That low uptake is why acetal is widely recommended for high-precision parts that must stay stable over time.

Choose nylon when the part’s job is wear + toughness + noise reduction, think impact-y mechanisms, sliding guides, or gears where you want a quieter material and can tolerate (or control) environmental drift.

Nylon vs UHMW-PE

UHMW is a monster for abrasion resistance, but it’s soft and springy, so it’s harder to hold tight dimensions and tends to produce long, stringy chips that wrap tools.

Nylon is easier to machine to shape and generally gives stiffer, more “part-like” geometry (threads, bosses, thin walls) with better tolerance potential assuming you manage humidity.

Nylon vs PETG / PEEK (Brief Positioning)

- PETG: Pick it when you want easy machining + stable cosmetic parts, but don’t expect it to beat nylon on wear/fatigue in moving mechanisms. (It’s more “housing/fixture” than “bearing.”)

- PEEK: When nylon’s temperature/chem limits aren’t enough, PEEK is the upgrade high Tg (~143°C) and high melt (~343°C) are why it stays stiff and stable in environments that soften nylon.

Cost, Availability, and When Nylon Is the Wrong Choice

Nylon looks inexpensive on the quote until you pay the hidden costs: scrap from warping, extra cycles for drying/conditioning, and the time sink of “machine → measure → wait → re-cut.”

If you’re cutting deep pockets or thin walls, nylon’s stress relaxation and moisture sensitivity can turn a one-pass job into a two- or three-pass workflow.

On the flip side, nylon can be extremely cost-effective when you minimize waste. Near-net cast nylon (cast blanks, rings, tubes, or custom shapes) reduces the amount of material you have to hog out, which lowers machining time and scrap compared with starting from standard solid shapes.

Cost Drivers by Nylon Grade

- Extruded PA6/PA66 rod/plate: cheapest and easiest to source for small-to-medium parts (fastest lead times, widest stocking).

- Cast nylon (monomer cast): often more economical at large diameters because you can buy (or cast) closer-to-finish forms (rings/tubes/near-net shapes), avoiding “center-cut” waste and reducing scrap.

- Glass-filled nylon (e.g., GF30): usually a premium vs unfilled, and it can increase tooling cost because the fibers are abrasive (carbide/diamond/DLC become more attractive in production).

- PA12: typically carries a premium price but often pays back through lower moisture uptake and better dimensional stability in precision work (especially medical/lab fixtures and tight-fit parts).

When to Avoid Nylon for Machining

No-go zones (unless you redesign the spec/process):

- High-precision fits in variable humidity where you can’t define/hold a conditioning state (nylon will equilibrate and move).

- >120°C continuous exposure unless you’re explicitly using a heat-stabilized/high-temp polyamide system; many “under-hood” polyamide solutions rely on thermostabilization packages to survive sustained heat.

- Strong acids / oxidizing agents: nylon is commonly listed as vulnerable to strong acids and oxidizers verify with a chemical-resistance chart for your exact reagent, concentration, and temperature.

Sustainability, Recycling, and future use of Machined Nylon

By 2026, two sustainability pathways have become main stream in engineering procurement: bio-based long-chain polyamides (notably PA11 and PA610, often derived from castor oil feedstocks) and chemical recycling of Nylon 6 back to caprolactam for re-polymerization into new PA6.

For companies with “green mandates,” that matters because nylon now has credible routes for both renewable content and closed-loop recycling, which many engineering plastics still lack at scale.

Final checklist

- Will humidity vary in service and is the tolerance defined for the conditioned state?

- Can you reduce scrap by buying cast/near-net blanks instead of machining from solid?

- Is the environment >120°C continuous or chemically aggressive (acids/oxidizers)?

- Do you need bio-based or chemically recycled PA6 to meet sustainability requirements?

FAQs

How do I stop nylon from melting or “smearing” while cutting?

Nylon has a low melting point (approx. 220–260°C) and poor thermal conductivity, causing heat to build up at the tool tip.

- The Fix: Use extremely sharp high-positive rake tools (10–15°) and maintain moderate spindle speeds. Compressed air or mist cooling is preferred over heavy flood coolant to prevent thermal deformation without causing swelling.

Why are my nylon parts changing size after I finish machining them?

Nylon is hygroscopic, meaning it absorbs moisture from the air, which leads to dimensional expansion—sometimes up to 2.5%.

- The Fix: Pre-dry raw stock at 80–90°C for 8–12 hours before machining. For high-precision parts, perform an annealing step after roughing to relieve internal stresses and stabilize dimensions before the final pass.

Should I use Nylon 6 or Nylon 66 for my project?

Choosing between these two most common grades depends on the environmental and mechanical requirements of the part.

- Nylon 6 (PA6): Better impact resistance and toughness; often cheaper and easier to process but absorbs more moisture.

- Nylon 66 (PA66): Preferred for metal replacement due to its higher tensile strength, stiffness, and heat resistance. It also has slightly better dimensional stability in humid conditions.

How can I manage the long, “stringy” chips that tangle around the spindle?

Unlike metals, nylon produces continuous, flexible chips that don’t naturally break, which can ruin surface finishes or jam equipment.

- The Fix: Use single-flute or double-flute tools to provide more space for chip evacuation. Implementing “peck” cycles during drilling and using high feed rates (0.1–0.4 mm/rev) can help force chips away from the workpiece.

What is the best way to clamp nylon without crushing or deforming it?

Nylon is much more flexible than metal, and standard high-pressure clamping can easily distort the part, leading to inaccurate cuts once released.

- The Fix: Use soft jaws or vacuum chucking to distribute clamping force evenly. If using a vise, tighten just enough to secure the part; for thin-walled components, consider internal supports or fixtures to maintain the part’s shape.